By Jose Caballero, International Institute for Management Development (IMD); The Conversation

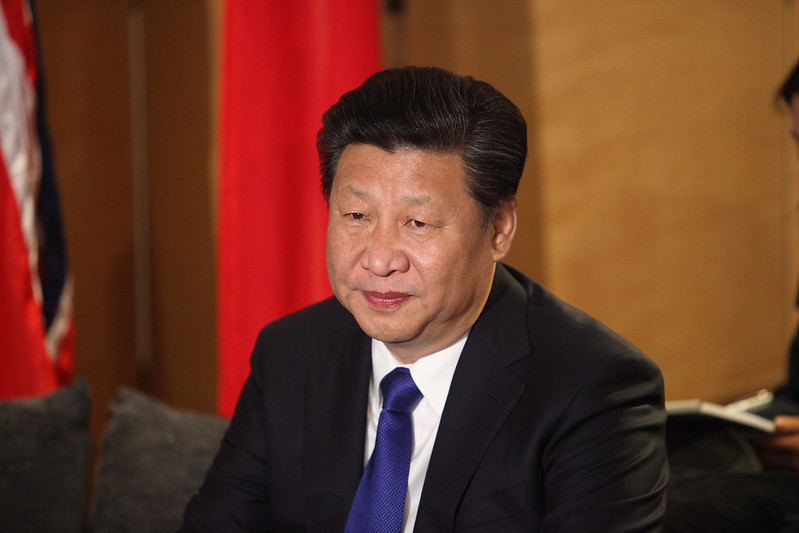

FILE: President of China, Xi Jinping in London, 19 October 2015. (Photo by Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office/Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Within days of Donald Trump’s election win in November 2024, China’s president Xi Jinping was at a ceremony opening a deep-water port in Peru as part of a “diplomatic blitz” through Latin America.

Xi’s presence was a symbol of China’s rising influence in the region. The Chinese-funded (£2.8 billion) Chancay port represents an expansion of the relationship between China and Peru. The two countries also signed an agreement to expand free trade. Xi said this was the beginning of a maritime version of China’s belt and road initiative, to expand its worldwide trade and influence.

The first Trump administration opted for a confrontational stance towards many countries in the region, including Peru. This ultimately pushed it to deepen its alliance with China. Beijing saw the opportunity, through favourable trade deals and investments, to position itself as a more reliable and beneficial partner than Washington.

In the last 20, years China has dramatically expanded its role as a top trading partner for Latin America. In 2002, trade between China and the region was worth US$18 billion (£14.34 billion), that amount increased to US$500 billion by 2023. In the first two months of 2024, China’s exports to Latin America increased by 20.6%.

Trump’s first term was widely seen as driving Latin American nations away from US values and alliances and towards China. Brazil, for example, saw trade with the US drop to its lowest level for 11 years, while trade with China grew significantly. Joe Biden did little to improve relations.

Trump’s campaign rhetoric signals that the upcoming administration will continue that trend. And China is certainly ready to build on its partnerships in the region if, and when, opportunities arise.

The Trump administration is likely to be focused on immigration and drug trafficking, as well as trade. For instance, Mexico is more likely to become a policy priority, because of illegal immigration, than Brazil.

Trump may look for regional allies whose policies seem more aligned with his own. Argentina’s president Javier Milei and El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele seem likely candidates, with their form of populism echoing some of Trump’s.

Despite efforts by Brazil’s president Jair Bolsanaro to work with Trump when they were both in power, and to echo Trump’s soundbites, trade between the two nations fell. Significantly, during Trump’s term of office three nations – the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Panama – withdrew recognition of Taiwan as a sovereign country, publicly shifting allegiance to Beijing and away from US-backed Taipei.

What next?

In 2025, countries with close ties with China could become targets for the Trump administration. Trump has threatened to increase tariffs on Chinese goods and outlined his tough China policies as part of his “America first” agenda. China may see the Chancay port as a back door to the US market, and possibly a way to avoid rising US tariffs. So Peru could become a trade-relations battleground.

Meanwhile, Trump’s America first policy, prioritising US interests, could also result in the reduction of regional aid.

Reduced US support might lead Latin American countries to seek even stronger ties with China. The latter has already been actively offering economic investments and supporting infrastructure projects through programmes related to the belt and road initiative over the past decade. Argentina has even become the base for a Chinese space station.

Belt-and-road-related projects are often seen as more attractive compared with aid and investments from western countries, including the US, as they come with fewer demands on the country receiving the investment.

Trump’s potential disengagement from multilateral organisations, such as Nato and the World Bank, could also strengthen China’s influence, globally. This US position would reduce its capacity to shape international norms and policies, leaving Latin American nations with fewer reasons to side with Washington.

Latin American countries, which often rely on multilateral institutions such as the Inter-American Development Bank for economic and political support, could turn to China for increased investment. China’s diplomatic efforts, including high-level visits and participation in regional forums, continue to rise, signalling its intent to strengthen ties with Latin America.

Strong economic relations with China will probably remain appealing to Latin American countries. Particularly so for those that have experienced economic instability in the post-pandemic period and are looking for new avenues of growth and development.

Importantly, China’s investments in the region’s infrastructure and energy sectors have already been substantial in the last decade. They have provided much-needed capital and technology transfers. Such investments have not only boosted local economies but also strengthened diplomatic ties, positioning China an important partner in the region’s development.

China v US

Another aspect of China’s foreign policy that can be attractive to Latin American countries is its non-interventionist approach. This policy emphasises respect for sovereignty and the right of countries to choose their own development paths.

China presents itself as an alternative to traditional western powers. This enables China to portray itself as a fellow developing economy, suggesting a sense of solidarity with Latin American countries. This contrasts with the US’s complex history of intervention in the internal affairs of many of the region’s economies.

As Trump continues to emphasise a more isolationist and protectionist approach, countries in Latin America may find China’s approach more compatible with their own policies.

The hostile rhetoric towards many Latin American nations, particularly over immigration, during the first Trump term has left those nations expecting something similar this time. China appears poised to make even more of those opportunities.![]()

Jose Caballero, Senior Economist, IMD World Competitiveness Center, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.