By Ramona Alaggia, University of Toronto; The Conversation

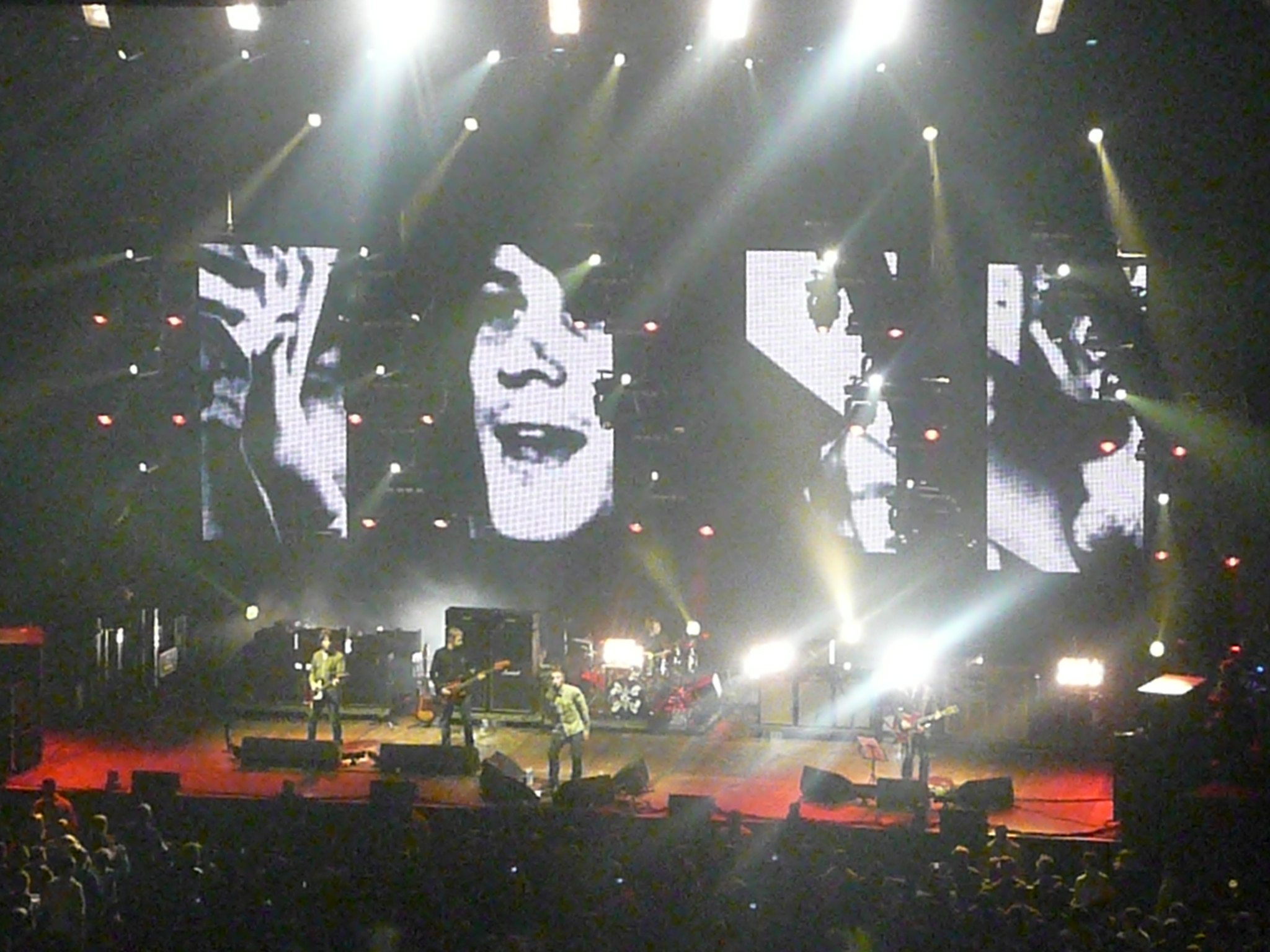

We only need to turn to the stories of the alcohol- and drug-fuelled antics that were part of the Oasis tour scene of the past to remember at least part of the reason why the band broke up. (File Photo: angela n./Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Is it possible that Liam and Noel Gallagher of Oasis have resolved their longstanding sibling feud well enough to be able to mount, and follow through on, a world concert tour after 15 years of estrangement?

And if so — does that mean our own sibling feuds can be healed?

No one’s 20s and 30s look the same. You might be saving for a mortgage or just struggling to pay rent. You could be swiping dating apps, or trying to understand childcare. No matter your current challenges, our Quarter Life series has articles to share in the group chat, or just to remind you that you’re not alone.

Read more from Quarter Life:

- How to know when it’s time to start therapy

- How to resolve friendship tension like Lorde and Charli XCX

- Are you a Destiel stan? There’s so much more to ‘shipping’ than wanting characters to kiss

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the antagonism between the Gallagher brothers resulted in epic confrontations that included physical blows on and off stage.

It seemed unimaginable that such a renowned sibling feud would end — and then suddenly the “guns fell silent” and the brothers announced a long-awaited Oasis reunion tour.

Sibling feuds aren’t unusual

The reunion offers an excellent opportunity to examine what it takes to resolve a sibling feud permanently, when you’re young enough to prevent it from becoming a lifelong estrangement.

First, when it comes to siblings, it’s important to know that conflict is a natural and normal part of family life and contributes to developing relationship skills. Sibling rivalry and feuds aren’t unusual — we probably all know someone who’s experienced one — and are intricately intertwined in the complexities of the wider family system.

Seminal research into family dynamics by American psychiatrist Murray Bowen found that families operate in patterns of interactions that they can become stuck in.

Without intervention, like a brief course of psychotherapy, family members can repeat dysfunctional patterns throughout their lives.

Abuse, violence

In the case of the Gallagher brothers, their family environment featured abuse and violence used to express anger and frustration.

There was little evidence of healthy conflict resolution in the home where the Gallagher brothers grew up, as both Noel and their mother were often abused by their father.

Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura’s social learning theory speaks to the powerful influence of relationship modelling in those formative years of childhood development. Growing up in a home where both physical and emotional abuse are normal leaves a strong maladaptive impression on how adults deal with anger and frustration.

As children, we often mimic these behaviours, sometimes well into our adult lives. This doesn’t mean all kids who grew up in abusive homes go down the path of dysfunctional relationships — many can and do rise above their circumstances and break the cycle of violence in adulthood.

Important turning points

My research has found people who grew up in abusive homes can break that cycle via turning points — life transitions that provide potential opportunities for resilience-building. These turning points — which can include meeting a positive life partner, the birth of a child or the death of a parent — may account for those who are able to escape the downward spiral. These types of life events can activate a new world view or insights into living a better life.

Changing how you deal with conflict in current relationships, including with your siblings, requires undoing the dysfunctional, internalized relational modelling of your childhood.

Insight, self-awareness to do and be better, and therapy are often necessary to change those ingrained patterns and pre-conditioned responses.

Dealing effectively with a high degree of conflict in a sibling relationship — like we’ve witnessed with the Gallaghers and another high-profile brother feud between Britain’s Prince William and Prince Harry — most likely requires an intervention of some sort to heal long-standing animosity.

How counselling can lead to resolution

If Noel and Liam, William and Harry — or you and your estranged sibling — seek help to resolve longtime feuds, intervention dyadic counselling would likely be part of the process.

That entails learning and practising conflict resolution strategies in therapy sessions. Models of conflict resolution strategies almost always include practising the following principles: (open) communication; active listening; reviewing options; collaboration; compromise; and agreeing on a win/win solution. Apologizing and avoiding blaming statements are part of the exercises.

Most importantly, learning to regulate strong negative emotions is at the core of this type of therapy. That includes finding tools to deal constructively with anger, jealousy and fear to avoid being negative and escalating conflict cycles.

Cognitive behavioural techniques, meditating and mindfulness, breathing and counting are all tools employed to de-escalate rising emotions by activating the rational, calm region of the brain.

The toxic role of drugs and alcohol

Practising abstinence in terms of substances is also advised, since substance use can be a disinhibiting factor.

We only need to turn to the stories of the alcohol- and drug-fuelled antics that were part of the Oasis tour scene of the past to remember at least part of the reason why the band broke up. Band members quit as a result of the brother’s toxic relationship well before the final split in 2009.

Drug and alcohol abuse causing problems for musical acts isn’t unusual — American rock band Jane’s Addiction is the most recent casualty.

What will make this Oasis tour work and the brothers to remain reunited? How can you ensure your own sibling feud doesn’t become a lifelong and stressful feature of your own life?

Booster therapy sessions (in Oasis’s case, this would mean having an on-tour counsellor), mediation sessions for when conflicts arise and staying sober and clear-headed whenever possible are good strategies for success.![]()

Ramona Alaggia, Professor, Social Work, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.