Headline

Is China preparing for a war over Taiwan, or has the west got it wrong? Here are the indicators

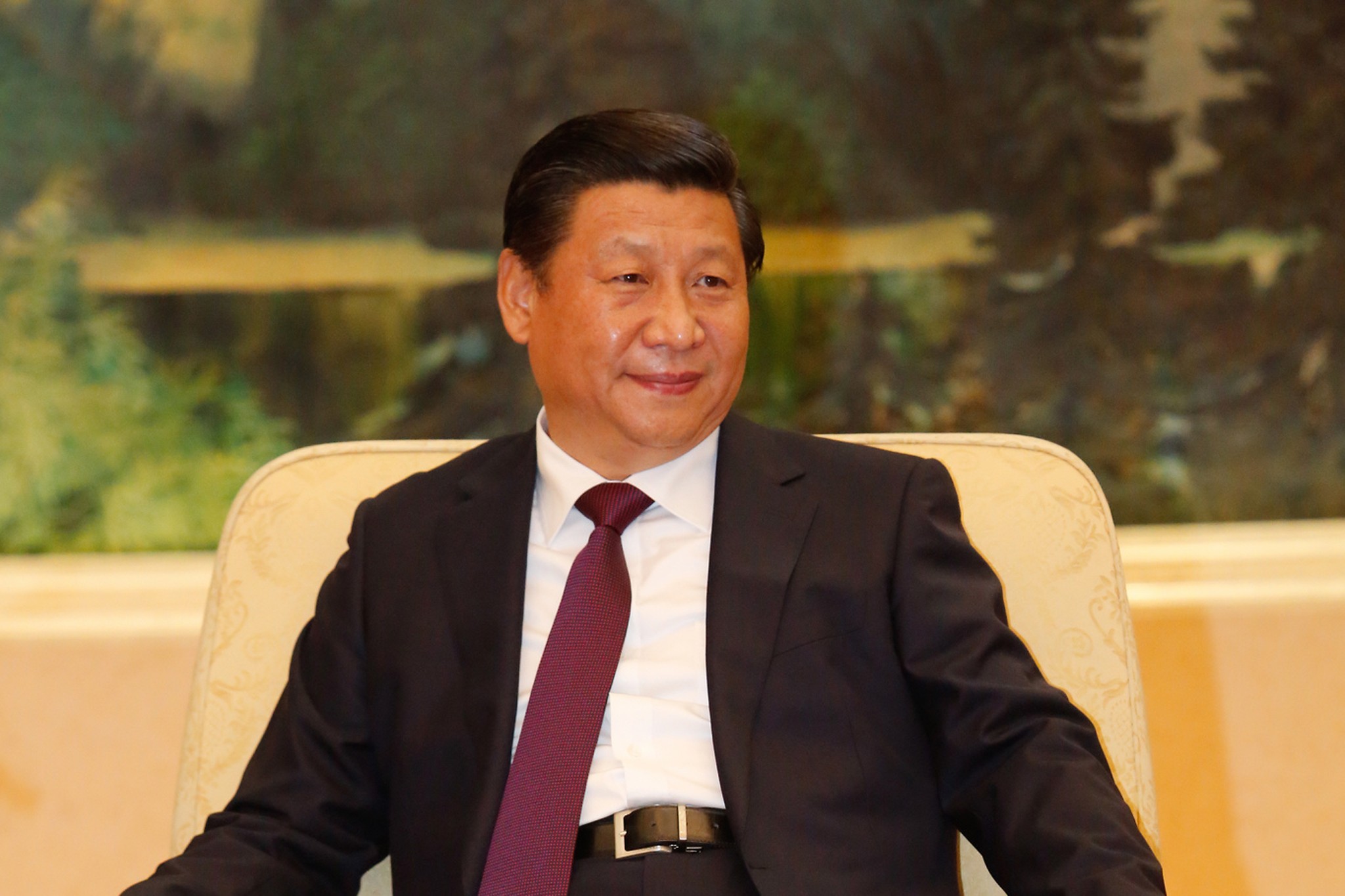

In his New Year’s address China’s president, Xi Jinping, stated that Taiwan would “surely be reunited” with China. (File Photo: Global Panorama/Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

At a time when Russia has been making gains in Ukraine and the Middle East appears to be on the brink of further regional conflict, a China-US military stand off is the last thing the world needs.

At first glance however, it might appear that China is preparing for a long-term conflict with the US over Taiwan, the self-governing island of 24 million people, which the mainland claims.

In his New Year’s address China’s president, Xi Jinping, stated that Taiwan would “surely be reunited” with China. This is particularly significant as it comes days ahead of Taiwan’s national election on January 13. The result which may deliver a more pro-Beijing government opting for closer ties, or what is currently looking more likely a Taiwanese leader who wants to keep Beijing at arms length.

The election will see the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) face off against the conservative Kuomintang (KMT). The DPP’s candidate, Lai Ching-te, who has been leading in the polls, has often been described as a more outspoken advocate of Taiwanese independence than his predecessor, the outgoing Tsai Yingwen, who took a more diplomatic approach, believing there was no need to state her support for independence as the island was a sovereign nation.

Any shift or pro-independence statement is likely to be seen by Beijing as a prompt for military action, since a formal declaration of independence is a red line for Beijing. In contrast, the KMT is seen as closer to Beijing. The US has traditionally supported Taiwan’s semi-independent status and sees it as a convenient regional ally. Coupled with the intensification of Chinese military flights around Taiwan’s airspace, all of these elements point to Taiwan as a potential trigger for a conventional US-China conflict.

Other key indicators

There are other key indicators to watch out for. The Chinese military has expanded and modernised over the past five years, and its advances in hypersonic missile technology puts Beijing at an advantage, as the US hasn’t yet deployed an equivalent.

Also significant is the growing perception of the US as an enemy among the Chinese public, part of a government narrative, especially since 2017. This is also a common theme among Chinese netizens as well, many of whom tend to be more nationalistic than the government is.

Technical battles

The US and China are already engaged in an economic and technological competition. This has continued despite the apparent thaw in relations at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in 2023, with the US and Chinese presidents sitting down for a four-hour chat, and agreeing to resume military-to-military communications which can avoid accidental military escalation.

In doing so Biden signalled he may be prepared to appeared to edge away slightly from his hardline policies to reduce dependence on China’s technology. His administration has not allowed US chip manufacturers to sell to China as well encouraging its allies to block the sale of hi-tech chip making exports. Dutch manufacturer ASML’s cancellation of its shipments of chip-making machinery to China, was attributed to pressure from Washington. A competition for economic and technological supremacy is already well under way.

This China-US competition is akin to the US-Japan tension of the 1980s and early 1990s, where Japan’s economic development and technological prowess caused notable concern among US policymakers to the extent that by the late 1980s, Japan was seen as a bigger challenge than the USSR.

But, while Beijing has adjusted to the new reality of an increasingly confrontational China-US relationship, this does not mean that China is definitely keen to start a long-term conflict. China is adjusting to massive challenges within its struggling economy, which makes Beijing somewhat reluctant to move to a war footing, despite its confrontational rhetoric.

Both sides have reservations

China’s significant industrial capacity and the reduction of western military stockpiles caused by the war in Ukraine, mean a conflict with China is something that the US can ill afford.

This was further underlined by several simulation exercises of a Taiwan conflict by the US military in 2020. They discovered that nine out of ten of the possible outcomes ended in a US defeat. So, a potential conflict with China poses a notable challenge for American power.

It’s clear that the present crises have provided an opportunity for China to gain understanding of current military challenges, as well as delivering some benefits. The conflict in Ukraine has provided China with several economic benefits, most notably in the form of greater access to Russian oil and gas, that had been the lifeblood of many European industries which Chinese firms have competed against. Equally, the tensions in the Middle East have served as a distraction for the US, which has had to focus more on the Middle East and Ukraine rather than fully committing to a confrontation with China. These crises have bought China time to prepare for what might come next.

These events show what knowledge China has accumulated. In the case of Ukraine, this is the importance of industrial production to warfare, with Russia’s industrial base enabling Moscow to continue with the conflict. It also highlights the limitations of Nato’s capabilities in supplying Ukraine.

The vulnerabilities of maritime power have been illustrated by the Houthi blockade of the Red Sea. This has demonstrated the possibilities of using missile and drone technologies to challenge stronger powers. In the case of China, this could take the form of Beijing using its anti-ship and hypersonic missile capabilities to challenge Washington’s naval strength.

What is becoming clear is that Beijing is increasingly preparing for a possible conflict, just in case. This preparation could help determine the outcome in Beijing’s favour.![]()

Tom Harper, Lecturer in International Relations, University of East London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.