Business and Economy

Bidenomics: why it’s more likely to win the 2024 election than many people think

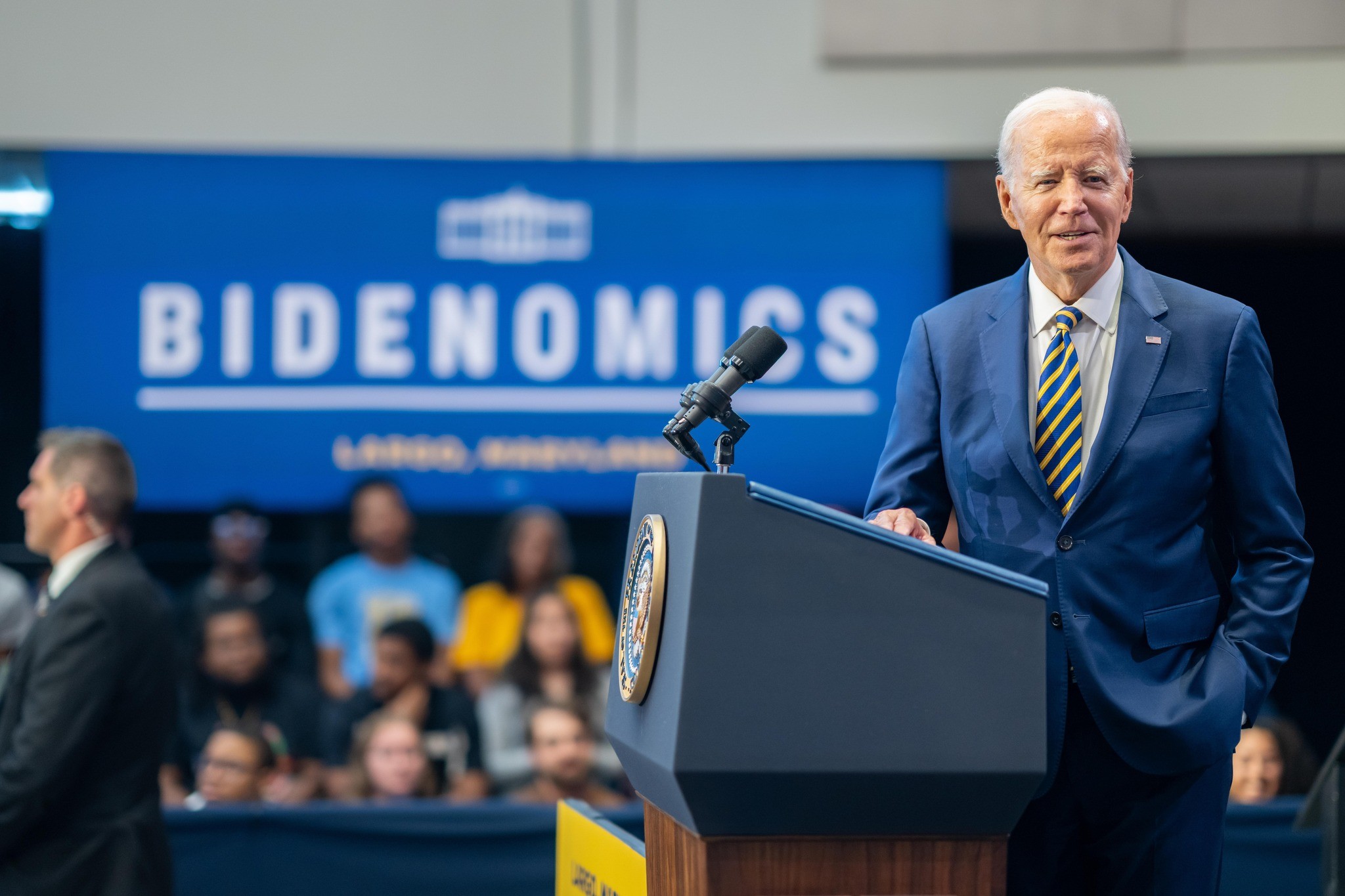

On investment, Biden’s approach fundamentally challenges the argument by the right that increasing public investment “crowds out” more efficient private investment. (File Photo: President Joe Biden/Facebook)

Joe Biden has come out fighting against perceptions that he is handling the US economy badly. During an address in Maryland, the president contrasted Bidenomics with Trumpian “MAGAnomics” that would involve tax-cutting and spending reductions. He decried trickle-down policies that had, “shipped jobs overseas, hollowed out communities and produced soaring deficits”.

Changing voters’ minds about the economy is one of Biden’s biggest challenges ahead of the 2024 election. Recent polling data suggested 63% of Americans are negative on the US economy, while 45% said their financial situation had deteriorated in the last two years.

Voters are also downbeat about Biden. In a recent CNN poll, almost 75% of respondents were “seriously” concerned about his mental and physical competence. Even 60% of Democratic and Democratic-leaning respondents were “seriously” concerned he would lose in 2024.

This appears a great opportunity for Donald Trump. He’s the clear favourite amongst Republican voters for their nomination, assuming recent indictments don’t thwart his ambitions.

Trump won in 2016 by capitalising on Americans’ economic discontent. Globalisation is estimated to have seen 5.5 million well paid, unionised US manufacturing jobs lost between 2000 and 2017. The “small-government” approach since the days of Ronald Reagan also exacerbated inequality, with only the top 20% of earners seeing their GDP share rise from 1980-2016.

Trump duly promised to retreat from globalisation and prioritise domestic growth and job creation. “Make America Great Again” resonated with many voters, especially in swing manufacturing states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. Winning these “rust-belt” states was crucial to Trump’s success.

These will again be key battlegrounds in 2024, but the economic situation is somewhat different now. There may be more cause for Democrat optimism than the latest polls suggest.

What is Bidenomics?

When Biden won in 2020, he too recognised that the neoliberal version of US capitalism was failing ordinary Americans. His answer, repeated in his Maryland speech, is to grow the economy “from the middle out and the bottom up”. To this end, Bidenomics is centred on three key pillars: smarter public investment, growing the middle class and promoting competition.

On investment, Biden’s approach fundamentally challenges the argument by the right that increasing public investment “crowds out” more efficient private investment. Bidenomics argues that targeted public investment will unlock private investment, delivering well paid jobs and growth.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has helped raise US capital expenditure nearer its long-term trend, although there’s a way to go. But what is really distinctive is the green-economy focus.

Almost 80% of the US$485 billion (£390 billion) in IRA spending is on energy security and climate change investment, through tax credits, subsidies and incentives. Much of the investments announced into manufacturing electric cars, batteries and solar panels, and mining vital ingredients like cobalt and lithium, are in the rust belt.

Meanwhile, Biden’s 2022 Chips Act is a US$280 billion investment to bolster US independence in semiconductors. With both acts backing domestic investment, the strategy concedes Trump’s point that globalisation failed blue-collar America. This is underpinned by other protectionist measures such as Biden’s “buy American” policy.

A whole series of measures aim to boost the middle classes. These include increasing workers’ ability to collectively bargain, and widening the maximum earning threshold for workers entitled to overtime pay from US$35,000 to US$55,000 – taking in 3.6 million more workers. As for promoting competition, measures include banning employers from using non-compete clauses in employment contacts.

The results so far

It’s too early to judge these policies, but the US economy has been relatively impressive under Biden. Over 13 million new jobs have been created, though much of this can be perhaps attributed to workers resuming employment after COVID. Unemployment is below 4%, a 50-year low, though similar to what Trump achieved pre-COVID.

The IMF predicts the US economy will grow 1.8% in 2023, the strongest among the G7. The US also has the group’s lowest inflation rate, although it rose in August. On the closely watched core-inflation metric, which excludes food and energy, the US is mid-table, though improving.

The federal deficit, the annual difference between income and outgoings, is heading in the wrong direction. It deteriorated under Trump, ballooned during COVID then partially bounced back, but is forecast to widen in 2023 to 5.9% of GDP or circa US$2 trillion.

Ratings agency Fitch recently downgraded the US credit rating from AAA to AA+. Fitch says the US public finances will worsen over the next three years because GDP will deteriorate and spending rise, and that the endless political battles over the US debt ceiling have eroded confidence.

Nonetheless, the other major ratings agencies have not made similar downgrades, and the widening deficit is mostly not because of Bidenomics. Tax receipts are substantially down because the markets have been less favourable to investors, while surging interest rates have increased US debt interest payments.

Overall, the economics signs are arguably moving in the right direction. An article co-written by business professor Jeffrey Sonnefeld from Yale University in the US, advisor to Democrat and Republican administrations, compares Bidenomics to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. It argues:

The US economy is now pulling off what all the experts said was impossible: strong growth and record employment amidst plummeting inflation … the fruits of economic prosperity are inclusive and broad-based, amidst a renaissance in American manufacturing, investment and productivity.

The Democrats know they must make this case to win in 2024. To compound Biden’s Maryland speech, there are plans for an advertising blitz in key states. Of course, the party may yet back another candidate, if they are thought more likely to win – currently Biden and Trump are neck and neck.

One consolation to the Democrats is that voters’ gloom is partly related to interest rates, which are probably close to peaking. Anyway, recent polling suggesting voters view the economy as the paramount issue is arguably good news: it means that Republican efforts to shift the narrative towards the culture wars are less likely to win an election.![]()

Conor O’Kane, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.