Lifestyle

Why old, shared dorms are better than new, private student residences

As students globally prepare for university, many contemplate where to live or prepare to move into new accommodations. (Pexels Photo)

As students globally prepare for university, many contemplate where to live or prepare to move into new accommodations. Students are faced with a variety of new options, different from their parents’ dorm rooms.

As universities have become more commercialized, they are entering into partnerships with developers, banks and marketing professionals that favour apartment construction, emulating units of the condo boom.

Enrolments in Toronto universities have been on the rise in the last two decades, at the same time the whole city is navigating a housing affordability crisis including a gruelling rental market.

Our recently published study, involving all 41 of Toronto’s university residences, found that in the past 30 years, newer residence halls that have been built increasingly stress privacy over communal spaces. Previous research has found a lack of student socialization spaces negatively affects students’ academic performance and well-being.

Space affects academic performance and well-being

Living on campus has historically been associated with better grade point averages (GPAs) and well-being. Firstly, students’ proximity to campus matters for developing positive relations with faculty and with the campus community. Secondly, common everyday residence life activities and chance encounters with peers encourages students to meet new people, to socialize and build resilient friendship support networks.

Paradoxically, both universities with private partners and private developers alone are marketing increased privacy in student accommodations, in response to perceived demand. Many privacy-oriented apartments house only one or two students, but privacy is a questionable benefit for students. Recent investigations have concluded living with larger amounts of privacy has negative effects on students’ GPA.

In more private units, everyday common activities are reduced, and so is the probability of chance encounters and friendships that potentially increase GPA and well-being.

Measuring privacy

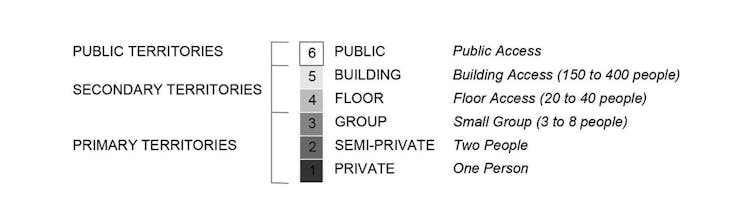

To study students’ experience of privacy and socialization, we developed a scale of six levels, called the Hierarchy of Isolation and Privacy in Architecture Tool (HIPAT).

(Shelagh McCartney and Ximena Rosenvasser)

These levels express the capacity of the spaces for students in their unit to be on their own (Level 1), to be with one other person (Level 2) and to be in a small group (Level 3).

HIPAT levels also signal students’ ability to have chance encounters with other students and university users in different areas on their floor (Level 4), in their building (Level 5) and in public spaces for all the student community (Level 6).

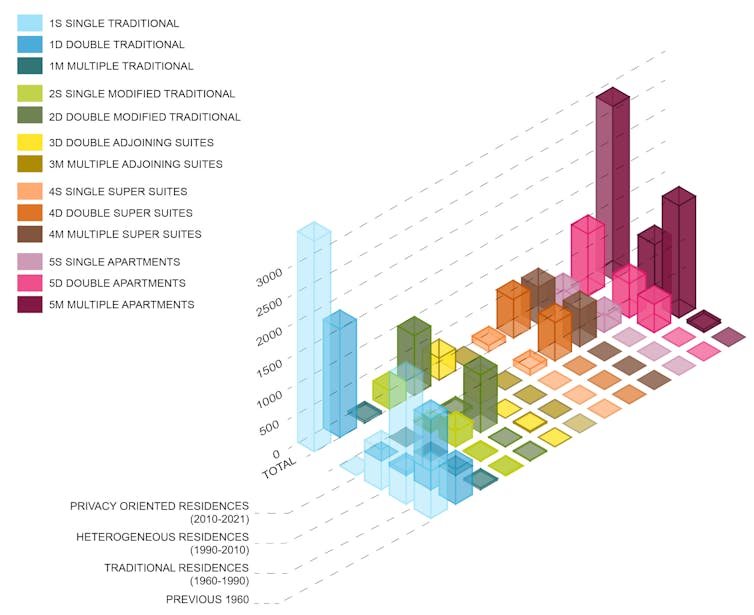

In a second study we created a taxonomy to classify students’ rooms and living facilities defined by their lived experience, called Housing Unit Classification (HUC).

(Shelagh McCartney and Ximena Rosenvasser)

This HUC classification defines each unit type by the HIPAT levels of each living facility (bedroom, bathroom, lounge and kitchen and dining) and levels of socialization available for each student.

Inhibiting resilient networks

Our research project analyzed all the university residences that were controlled or affiliated with Toronto universities. Over half the residences (23) were selected for more detailed study of privacy and socialization opportunities, and how they changed over time.

Describing the privacy and socialization spaces of each residence permits us to classify how much the built space of residences enable students to socialize with new people and create resilient networks. We delineated four time periods of residence design:

- 11.2 per cent of students today live in HUC Type 1 traditional rooms in residences built before 1960. These residences would be a small community of around 60 students living in a building that is a few storeys high.

(Shelagh McCartney and Ximena Rosenvasser)

- 26.3 per cent of students live in “traditional residences” built between 1960 and 1990, characterized by features like bedrooms (HUC Types 1 & 2) on both sides of a long hallway with common washrooms and lounges shared with the floor and dining space shared with the whole building, with around 200 to 300 students for each residence.

- 33.9 per cent of students live in residences built between 1990 and 2010 that combine traditional rooms and apartment units in the same residence (“heterogenous residences”). Compared with traditional residences, students have different living experiences in the same building.

- 28.6 per cent live in residences that were built between 2010 and 2021 and are privacy-oriented, with mostly suites and apartment units. Students living in these residences no longer share a washroom and are less likely to have a common dining experience with other people outside of their unit.

(Shelagh McCartney and Ximena Rosenvasser)

Reports on student housing construction show that there is a trend towards building more suites and apartments. These are not built with the common spaces of traditional residences that have historically facilitated socialization and been positively associated with higher GPA and well-being.

Privacy is not a luxury

Student residences built in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom over the past 20 years prioritize privacy and risk isolation to accommodate perceived student preferences. This trend is to the detriment of students’ social spaces, and should be questioned.

A student’s living situation is a key component of their university education. Universities should remain in the business of student housing. Universities and developers need to focus on building student housing that fosters community building in order for socialization and new relationships to occur.

Meeting students’ socialization needs is the first step towards a more egalitarian and successful university experience.![]()

Shelagh McCartney, Associate Professor, Urban and Regional Planning, Toronto Metropolitan University and Ximena Rosenvasser, Architecture and Urbanism Researcher, Toronto Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.