Lifestyle

Like father, like son: new research shows how young men ‘copy’ their fathers’ masculinity

This highlights the critical role fathers play in steering boys towards healthier ideas about masculinity. (Pexels photo)

Today’s men express their maleness in different ways. Some adhere to more traditional models of masculinity, characterised by beliefs in male superiority and endorsement of risky or violent behaviours. Others embrace more progressive stances.

But how do men develop their ideas, beliefs and behaviours in relation to masculinity?

Our new study addresses this question by focusing on one important factor influencing how young men express their masculinity – their fathers.

Our research set out to ask: do young men “copy” their fathers’ masculinity?

We found that young men whose fathers support more traditional forms of masculinity are more likely to do so themselves.

This highlights the critical role fathers play in steering boys towards healthier ideas about masculinity.

Measuring masculinity

We analysed data from 839 pairs of 15-to-20-year-old men and their fathers. These data were taken from a large, Australian national survey on men’s health.

The survey asked men a set of 22 scientifically validated questions about how they felt and behaved in relation to many issues around masculinity. For example, they were asked about:

- the significance of work and social status for their sense of identity

- their take on showing emotions and being self-reliant

- their endorsement of risk-taking and violent behaviours

- the importance they assigned to appearing heterosexual and having multiple sex partners

- and their beliefs about winning, dominance over others and men’s power over women.

Taken together, the answers to these questions offered us a window into whether the men participating in the survey adopted more of a traditional or progressive type of masculinity. They also enabled us to compare fathers’ and sons’ expressions of masculinity.

What we found

We found that, on average, young men are slightly more traditional in how they express their masculinity than their fathers.

On a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating high conformity to traditional masculinity and 0 indicating low conformity, the average masculinity score for young men was 44.1, and for their fathers, it was 41.

Using statistical models, we then examined whether there was an association between how traditional a father’s masculinity is and how traditional their son’s masculinity is. To make sure we isolated the effect of fathers’ masculinity, the models took into account other factors that may also shape young men’s expressions of masculinity. These included their age, education, sexual orientation, religion, household income and place of residence, among others.

The results were clear. Young men who scored highly on the traditional masculinity measures tended to have fathers who also scored highly.

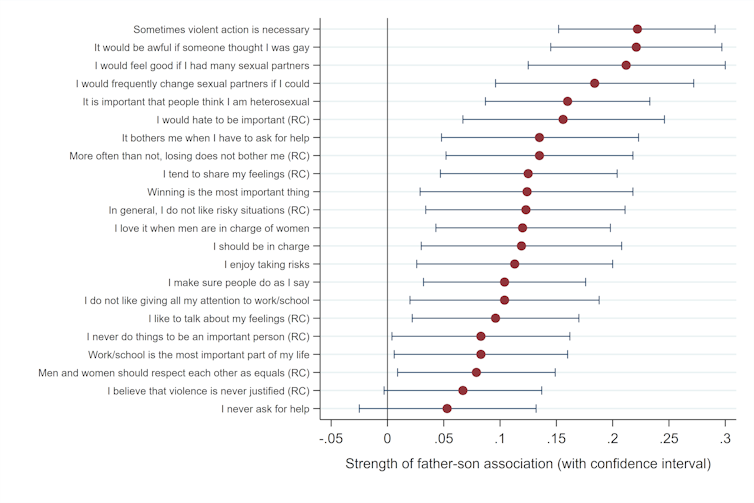

Francisco Perales et al, Sex Roles, Springer Nature, CC BY

We identified similar results for 20 of the 22 individual masculinity questions. The strongest father-son associations emerged for questions about the endorsement of violence, importance of appearing heterosexual, and desirability of having multiple sexual partners.

This indicates these aspects of masculinity are comparatively more likely to be “passed on” from fathers to sons.

What our findings mean

As is well-established, social learning is important in shaping young people’s attitudes and behaviours. While fathers aren’t the only influence, our study suggests young men learn a lot about how to be a man from their dads. This is an intuitive finding, but we had little empirical evidence of it until now.

Confirming that dads “pass on” their masculinity beliefs to their sons has far-reaching implications. For example, it goes a long way in explaining why traditional models of masculinity remain entrenched in today’s society. Our study indicates that breaking this cycle requires bringing fathers into the mix.

Policies, interventions and programs aimed at promoting healthy masculinity among young people are more likely to work if they also target their dads. This proposition is consistent with a growing body of programs focused on engaging fathers in positive parenting.

What’s more, our findings underscore the potential long-term effects of successful intervention. If a program manages to help young people develop positive masculinity, it’s likely that — as they themselves become fathers — their own children’s masculinity is also positively affected.![]()

Francisco Perales, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Social Science, The University of Queensland; Ella Kuskoff, Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course, The University of Queensland; Michael Flood, Professor of Sociology, Queensland University of Technology, and Tania King, Associate professor, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.