Lifestyle

Sex education review: controversial proposals risk failing young people

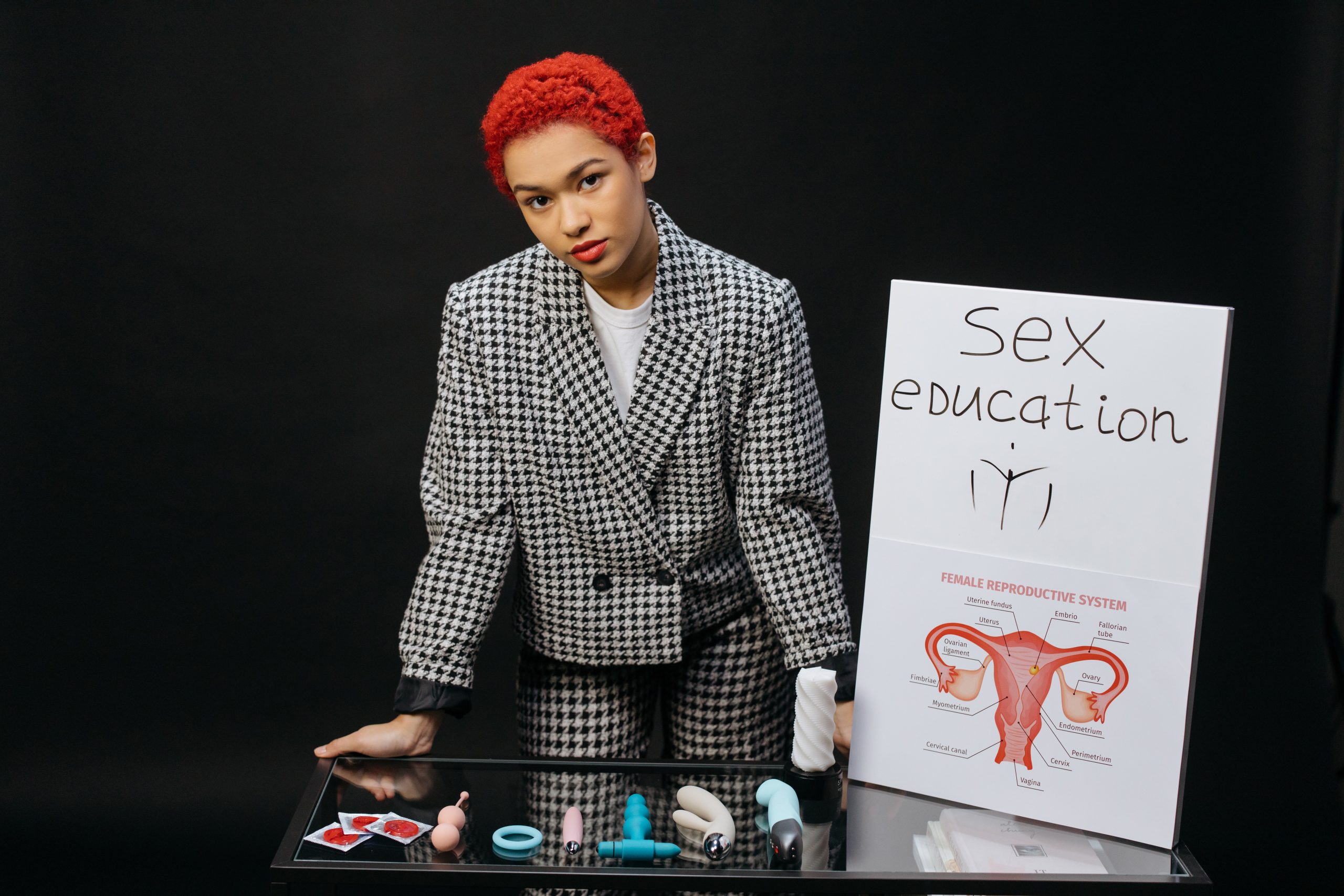

Sex education is vitally important. It helps young people navigate situations which may be full of anxiety and uncertainty. (Pexels Photo)

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has brought forward a planned review into sex education in English schools.

This is in response to concerns raised by Conservative MP Miriam Cates over sex education that is “age-inappropriate, extreme, sexualising and inaccurate” being taught in schools. Nearly 50 Conservative MPs signed a letter coordinated by Cates which called for a independent inquiry into the supposed delivery of inappropriate sex education content to young children.

A report on sex education in schools, commissioned by Cates, published in March 2023 and presented to Sunak, criticises numerous elements of current sex education teaching. The report was carried out by the New Social Covenant Unit, an organisation set up by Cates and another MP, Danny Kruger.

If followed, the recommendations in the report have the potential to roll back decades of significant progress in supporting children and young people and have adverse affects on their health and wellbeing.

Sex education is vitally important. It helps young people navigate situations which may be full of anxiety and uncertainty. It helps them recognise unwanted or inappropriate behaviour. Research has found that a lack of sex education is a risk factor for sexual abuse.

‘Age appropriate’

The report calls for “age appropriate” sex education, stating that “in some cases the only ‘age appropriate’ approach might be to not introduce the subject at all”. It holds that there should be clear parameters on what should be taught. However, government guidance already provides this, outlining topics and at what age ranges they should be taught.

There is also a danger in being too prescriptive. Different children and young people have different needs from their sex education lessons. For instance, if violent porn is being shared among a class of young people teachers have to act fast to help them deal with what they have seen, with consideration to consent and respect.

Fundamentally, sex education has to be realistic. It is highly likely that young people will see pornographic content and receive unwanted images at some point before they get to 18. This has to be addressed through safe sex education lessons.

Teaching children about relationships and sex often throws up moral issues. Sexual desire can be seen as an affront on morality, making sex something that has to be controlled and monitored. This, coupled with current perceptions of children, makes discussion of sex in schools difficult. This moral panic also makes sex education a valuable political pawn.

Discussing sex with children and young people is often, incorrectly, framed as encouraging sexual behaviour. But a plethora of research demonstrates that the more information young people have about sex the more likely they are to delay it.

The report commissioned by Cates questions a “sex positive” approach to sex education that seeks to reduce shame. It states that “‘sex positivity’ does not seem to tolerate other ethical systems of thought that favour restrictions, boundaries, see a purpose in shame, or which have moral codes that might exclude certain practices or oppose ‘sex positivism’ itself”.

But shame is incredibly damaging. Shame silences young people. It means that they do not seek information and support when they need it, putting themselves at risk. What’s more, linking sex to morality can increase feelings of shame.

LGBTQ+ students

The report also presents a worrying approach to sex education for LGBTQ+ and gender diverse children and young people. It states that LGBTQ+ matters take a “disproportionately dominant place in the curriculum”. But research suggests that sex education in the UK is predominantly delivered from a standpoint focused on heterosexual sex and relationships.

This means that LGBTQ+ children and young people lack relevant and affirming sex education. This lack has been linked to higher rates of STIs, HIV and even teen pregnancy among LGBTQ+ young people.

The report also questions teaching on issues relating to gender identity. It states that “…of particular concern is that a political and ideological bias in RSE teaching is promoting trans identification to school pupils”.

Research shows that transgender and gender diverse children face discrimination at school. But there is evidence that being in environments that are positive about gender and personal identity lead to improved health and wellbeing outcomes among this group.

Calls in the report for an emphasis on teaching the biological mechanics of sex – such as procreation and contraception – almost exclusively focuses upon sexual relations of cisgender and heterosexual young people. But decades of evidence shows that comprehensive and inclusive sex education results in positive mental health outcomes and safer school climates for all young people.

Also, a greater proportion of LGBTQ+ inclusive sex education leads to lower rates of poor mental health and reduced school-based victimisation for LGBTQ+ students.

We need to listen to young people

A crucial aspect missing from the report is the input of children and young people themselves. Young people want to engage in designing sex education that benefits them. They are often being taught what they already know.

Quite simply, we do not know what normal sexual behaviour is in children and young people and we need them to guide us in what they need and when. Good sex education should focus on their needs, rather than it being imposed upon them. It should be designed with young people and underpinned by research.

We must provide young people with sex education that keeps them safe. The recommendations in the report commissioned by Cates risk undoing over 20 years of valuable progress in helping young people make informed decisions about their own sexuality and relationships without shame.![]()

Sophie King-Hill, Senior Fellow at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham; Abby Gilsenan, PhD Candidate in the School of Social Policy, University of Birmingham, and Willem Stander, Research Fellow in the Department of Social Work and Social Care, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.