News

First the floods, then the diseases – why NZ should brace for outbreaks of spillover infections from animals

Many pathogens survive in the gastrointestinal tract of animals and are released in their feces. (File Photo: Flash Dantz)

When Cyclone Gabrielle hit New Zealand in February, it left a trail of destruction across the North Island. At least 11 people died, and more than 10,000 were displaced. Bridges were washed out (35 in the Hastings district alone), roads closed and communications cut.

With potable water and wastewater systems damaged and land covered in silt, there is another consequence that may yet appear – diseases, or more specifically, zoonoses that spread between animals and people.

Floods and their aftermath are a time of higher risk for disease spread. While we do not have much data specific to New Zealand, due partly to the difficulty of diagnosing and reporting diseases during times of crisis, we can use information from overseas to predict which diseases may flare up after floods.

First, the tummy bugs

The first group of diseases for which we expect to see a rise in case numbers soon after floods is gastroenteritis caused by water-borne pathogens. GPs in Auckland are reporting an increase in cases since the Auckland anniversary weekend floods.

Many pathogens survive in the gastrointestinal tract of animals and are released in their feces. Rain and floods facilitate their transmission by providing an environment through which they sometimes enter the food chain or water supply.

In 2016, Hawke’s Bay experienced a campylobacteriosis outbreak transmitted through the urban water supply that affected more than 6,000 people. The outbreak occurred just after heavy rain, which likely caused water contaminated with sheep feces to enter a bore.

Salmonellosis cases are also likely to rise during summer floods, aided by higher temperatures. The risk is particularly high as cases in dairy cattle have been steadily increasing during the past eight years.

Local branches of Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand in affected areas have been proactive in communicating these risks and prevention measures, including the importance of wearing protective gear during the cleanup.

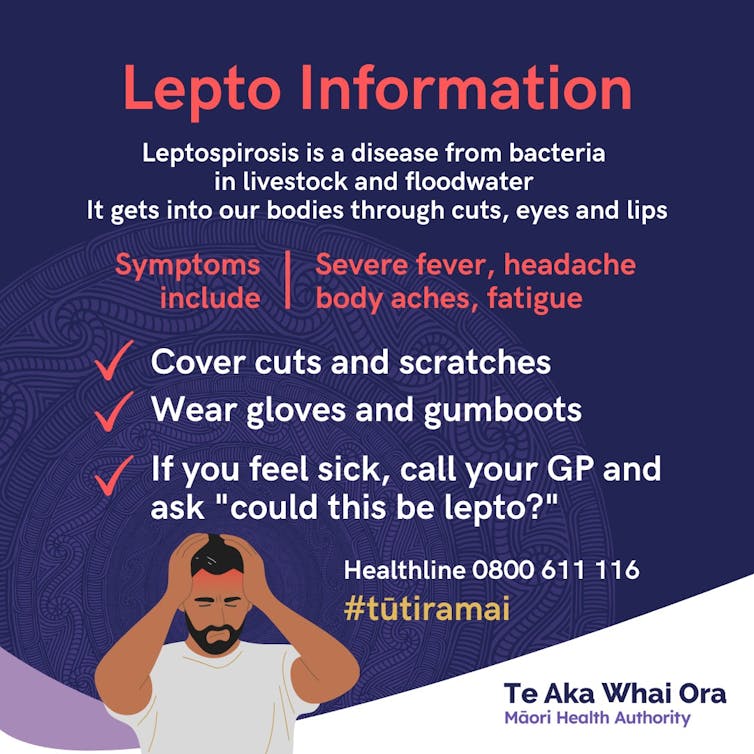

Then, leptospirosis

About a week to a month after floods, rodent-born disease outbreaks can start to appear.

Floods disturb the habitat of rodents, including rats, and they can be attracted to food waste around people’s homes. This was regularly observed after floods in Queensland last year and in Auckland earlier this year.

In New Zealand, our main concern is the bacterial disease leptospirosis. Brown rats carry one of the variants, livestock several others, and, once the bacteria are shed in the animals’ urine, they can survive in water and soil for several days. This ability to survive in flood water means the risk of infection is increased for all variants, including those traditionally associated with ruminants and pigs.

Auckland has reported an increase in leptospirosis cases in February, likely linked with the floods at the end of January. Hawke’s Bay was already a known leptospirosis hotspot that could worsen.

Te Whatu Ora ‐ Te Matau a Māui Hawke’s Bay, CC BY-ND

The clinical signs of leptospirosis can vary a lot and it is important people seek medical attention when they feel unwell as it can be treated with antibiotics. People can get infected through contact with urine or a contaminated environment, via the mouth or nose or uncovered skin cuts.

Leptospirosis outbreaks in dogs can also happen. While they are rarely a source of infection for people in New Zealand, dogs can act as sentinels. The New Zealand Veterinary Association (NZVA) provides advice to owners of companion animals.

Finally, the mosquitoes

New Zealand is likely (at least for now) safe from the final group of diseases emerging after floods: vector-borne diseases.

We don’t have the disease-carrying insects or viruses known to cause outbreaks, but our Fijian neighbours and many other countries often report dengue outbreaks after floods.

Climate change is making it easier for both the insect carriers and viruses to establish in New Zealand, so we should not ignore this as a potential future threat.

How to protect ourselves

Vaccination, early detection and treatment of livestock, which act as a reservoir for many of the pathogens above, are effective ways of protecting humans.

Cattle can be vaccinated against three variants of bacteria causing leptospirosis and four types of Salmonella. But vaccination does not cover all the strains and is more difficult in the current situation when fencing has been destroyed and some communities can only access veterinary medicine by helicopter.

The use of personal protective equipment and good hand hygiene for any outdoor activity that involves contact with animals or flood water and soil is the best way to prevent diseases. Rodent control, including rapid disposal of food waste, is also more important than ever.

It is important people seek medical care rapidly, both for themselves and their animals when they are unwell. This is how they can access appropriate treatment, but also how surveillance can happen, so New Zealand starts learning its own lessons on health risks associated with floods.

Our cities, population structures, farming systems and wildlife species are different from overseas, so having local data is crucial. This will help during the next heavy rain and floods – and there is no doubt there will be many more.

We would like to acknowledge the contribution by Masood Sujau.![]()

Emilie Vallee, Senior Lecturer in Veterinary Epidemiology, Massey University; Barry Borman, Professor, Massey University; Deborah Read, Associate professor, Massey University, and Masako Wada, Research Officer in Veterinary Epidemiology, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.