Health

Imagining COVID is ‘like the flu’ is cutting thousands of lives short. It’s time to wake up

Many have been infected multiple times, potentially exposing them to long COVID and other problems we are only beginning to understand. (Pexels photo)

It is difficult to understand the ease with which we have accepted a major proportion of the Australian population getting infected with COVID in just a matter of months. Many have been infected multiple times, potentially exposing them to long COVID and other problems we are only beginning to understand. In the past 75 years, only the second world war has had a greater demographic impact on Australia than COVID in 2022.

As of September 12, Australia had reported more than 10 million cases of COVID. Of those, 96% were reported in 2022, coinciding with a succession of various Omicron sub-variants and the removal of most protective measures. What’s more, the number of reported cases is probably an underestimate.

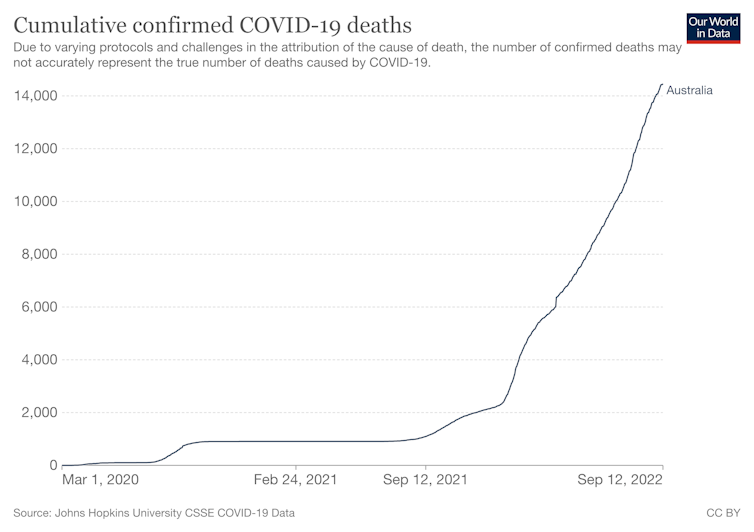

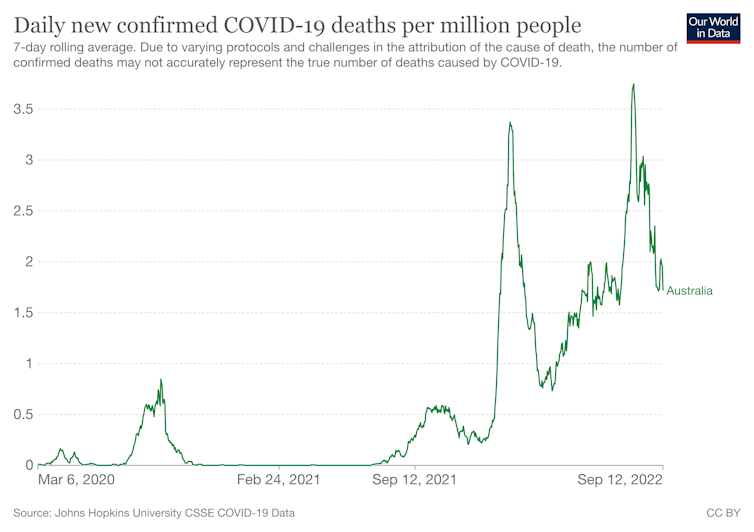

While the midsummer wave of Omicron led to the highest number of reported cases since the pandemic began, the subsequent winter waves have killed thousands more people.

Between January 5 and March 16 this year, 3,341 Australians died with COVID, compared with 8,034 between April 4 and September 16, with August being the most deadly month of the pandemic for Australia. One often forgotten impact of these deaths is that an estimated 2,000 Australian children have lost at least one parent as a result of the COVID pandemic.

Rather than national cabinet looking at pandemic leave and under pressure to cut isolation periods, what’s needed is a shared vision and a strategic COVID plan that acknowledges it is not “just like the flu”.

A disease evolving quicker than our defences

The deadly July-August wave happened despite greatly increased immunity from third- and fourth-dose vaccination, natural infection, and lifesaving therapies introduced in April this year.

In other words, Omicron has evolved faster than the tools we are using to combat it. So far in 2022, more than 12,000 Australians have died with COVID, six times the number of deaths in the previous two years.

This is a disease so significant it has reduced global life expectancy, one of the best measures of human development.

No other war or disease has done that in more than 65 years, not even the HIV pandemic. The global estimates have been reinforced in several countries, including the United States, where life expectancy has fallen by almost three years since 2019.

Changes in life expectancy only happen when very large numbers of people die “before their time”. In Australia there were 17% more deaths reported this year to the end of May by the Australian Bureau of Statistics than the five-year average. This does not count our most recent and lethal BA.5 wave.

The ABS report shows two things. First, COVID is killing large numbers of people both directly and indirectly. At this rate, we can expect to lose many more lives by year’s end. Second, people are dying earlier than they otherwise would have, meaning our life expectancy trajectory will take a hit.

Then there is all we know about long COVID and its effects on the lungs, heart, brain, kidneys and immune system. It affects at least 4% of those infected with Omicron, including those vaccinated and those with mild initial illness.

We are being warned to prepare for what is effectively a mass disabling event with no known cure or end point.

Not ‘like the flu’

How did we come to this point? A key reason we have become so complacent is the common narrative comparing COVID to influenza – in the sense that we should live with COVID in the same way we do with the flu.

The statistics demonstrate a different picture. From the start of this year to August 28, there had been just under 218,000 reported cases of flu and 288 deaths this year. There have been 44 times as many COVID cases and 42 times as many related deaths. (It is worth noting here authorities are urging caution when comparing this flu season to previous years, given COVID measures and changes in health behaviour.)

Around 1,700 people have been hospitalised with the flu this year. Yet on just one day in July, 5,429 COVID patients were in hospital.

In Australia, we have just had our worst COVID wave in terms of the number of deaths and people admitted to hospital, a wave that is ongoing with thousands still in hospital and around 360 people dying each week.

Government health advisers are warning of another COVID wave in the coming months. Independent MP Monique Ryan is calling for a national COVID summit and more transparency regarding planning. In contrast, this year’s influenza wave looks to be over.

Expendable lives

This has been a devastating year for older Australians. More than 3,000 residents of aged care facilities have died of COVID, triple the combined number who died in 2020 and 2021. As things stand, these lives appear invisible and expendable.

The most important discussion now is not about changes to any one intervention. It is one of overall strategy, one that focuses on reducing the spread of the virus.

Immunity from infection is, of course, real. It’s why people usually recover from infection, why waves disappear, and indeed what drives viral evolution to “escape immunity”.

But the more important questions are how much protection it offers, for how long, and at what cost? We now know immunity from Omicron infection is relatively poor and short-lived and is outpaced by rapid viral evolution, even in the face of vaccination.

Although vaccination vastly reduces the risk of serious illness, waves of infection continue to sweep through large populations, with many susceptible to reinfection within months. This continues to damage our short and long-term health, our health system, and our society.

COVID is nothing at all like the flu. It is causing a vastly worse scale of damage. We must change our tactics to dramatically cut transmission. In addition to a more vigorous campaign to increase vaccine booster coverage, we need to invest in indoor ventilation and actively promote the benefits of wearing high-quality masks in crowded indoor settings.

And we need a powerful messaging campaign to wake us from our “just like the flu” slumber.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.