Health

Monkeypox: World Health Organization declares it a global health emergency – here’s what that means

The head of the WHO, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, broke the deadlock and declared the outbreak a PHEIC. (File Photo: Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus/Facebook)

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the current monkeypox epidemic a global health emergency.

The committee of independent advisers who met on Thursday July 21 2022, were split on their decision on whether to call the growing monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) – the highest level of alert.

The head of the WHO, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, broke the deadlock and declared the outbreak a PHEIC. This is the first time the WHO director general has side-stepped his advisers to declare a public health emergency.

The first case of monkeypox was reported in a child in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire) in 1970. Since then, outbreaks have generally been small and traceable to an individual who recently returned from a country where the virus is endemic – that is, countries in west and central Africa. But the current outbreak is unlike any previous one outside of Africa in that there is sustained person-to-person transmission of the infection.

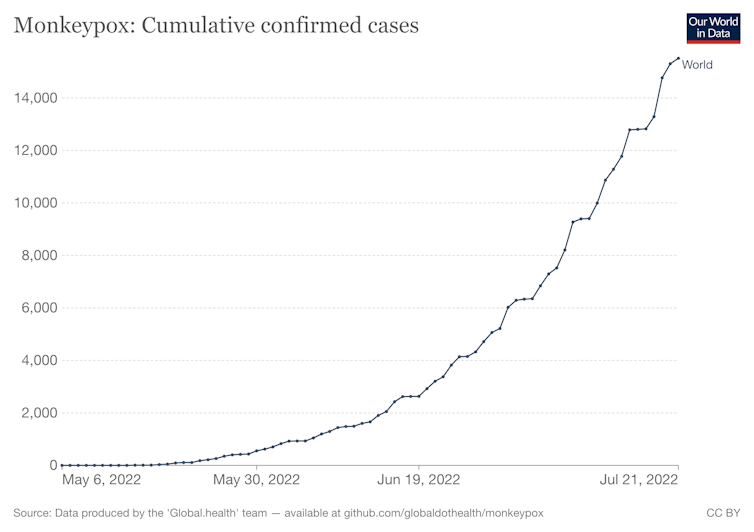

As of July 22, there have been 16,593 confirmed infections in 68 countries that have not historically reported monkeypox. Most infections have been reported from Europe. The large majority of infections have been in men who have sex with men, especially men who have sex with multiple partners.

Models presented to the WHO suggest the average number of people infected by a single infected person (the so-called R nought – remember this from the early days of the COVID pandemic?) is between 1.4 and 1.8 in men who have sex with men, but less than 1.0 in other populations. So although occasional infections can spill over into populations other than men who have sex with men, further significant spread is unlikely.

In Europe, in recent weeks there has been a slowing in the rate of increase in new monkeypox cases each week. The large majority of infections are still occurring in men who have sex with men.

In the UK, 97% of cases are in men who have sex with men, but it does look as though the rate of growth in the epidemic has fallen to zero or even become negative in recent weeks. But it is plausible that the apparent dip in new infections is the gap between consecutive waves.

Experts have recently been debating whether monkeypox is now a sexually transmitted disease. Even though monkeypox is undoubtedly spread during sex, labelling it as an STD would be counterproductive, as the infection could spread through any intimate contact, even when wearing condoms or without penetrative sex.

Our World in Data, CC BY

For and against declaring a global health emergency

Broadly, the WHO’s emergency committee arguments in favour of declaring a global health emergency included that monkeypox satisfies the requirement of a PHEIC under the WHO’s International Health Regulations: “an extraordinary event, which constitutes a public health risk to other States through international transmission, and which potentially requires a coordinated international response”.

Added to this are concerns that in some countries there is likely to be substantial under-reporting of case numbers, the occasional reports of infections in children and pregnant women, concerns that the infections could become endemic in human populations or be reintroduced into at-risk groups even after the current monkeypox pandemic is over.

Arguments against declaring it a global health emergency included the fact that the large majority of infections are currently being seen in just 12 countries in Europe and North America, and there is evidence of cases stabilising or even falling in those countries.

Almost all cases are in men who have sex with men and who have multiple partners, which provides opportunities to stop transmission with interventions targeted at this group. Another argument is that the severity of the disease outside appears to be low.

Although the emergency committee was not able to reach a consensus, Tedros took the decision to declare a PHEIC.

This declaration of a global health emergency will probably not lead to much change in control activities in the most affected counties outside of Africa. However, it may stimulate those countries that have seen few cases so far to ensure their health systems are better able to manage if the infection does spread within their countries. Hopefully, it may also stimulate funding for research and improvements in the capacity in endemic countries to manage the disease.![]()

Paul Hunter, Professor of Medicine, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.