News

The Jan. 6 insurrection showed that performance crime is becoming increasingly popular

The filming and uploading of performance crimes during the Capitol riots is only one piece of the media puzzle. (File Photo: Andy Feliciotti/Unsplash)

To film oneself committing a crime might seem a guileless act of self-incrimination, but it’s becoming increasingly popular. Take the Jan. 6 insurrection as a case in point.

With 874 people arrested on charges from disorderly conduct to seditious conspiracy, many were apprehended because of video or photos shared online. This is considered performance crime: the performance of criminal activity in which filming and sharing it with an audience is intrinsic to the crime itself.

The hearings held by the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol have brought to light high-level closed-door conversations rarely shown in the media. In this emerging context, as a long-time researcher on alternative and digital media, my study of performance crime can help us understand both the importance and inadequacies of social media news feeds.

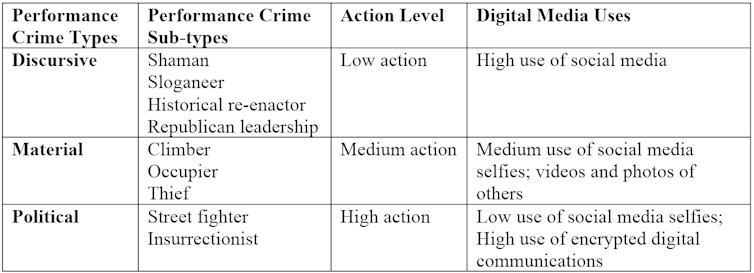

Performance crime participants may be considered self-surveillant subjects, those who effectively participate in and submit themselves to digital surveillance by uploading photos and videos of their actions. Self-surveillant subjects in the Capitol riots participated in performance crimes I have categorized as discursive, material and political.

Text-based performances

Discursive performance crimes were low-level actions that included textual (placards, signs, graffiti), visual (costumes, hats, T-shirts, tattoos) and auditory (slogans, shouting) performances in four sub-categories:

- Shaman — based on the QAnon Shaman — which are performances based on adopting conspiracy theories.

- Sloganeers — which included the use of slogans like “Hang Mike Pence” and “#StopTheSteal” — based on violence and disinformation.

- Historical re-enactors — who dressed up as historical or fictional characters, like George Washington, Lady Liberty, Uncle Sam and Captain America — representing the nostalgia of a mythological white supremacist American past referenced in Trump’s Make America Great Again slogan.

- Republican leaders — calls-to-arms espousing violence and aggression for Jan. 6, such as Trump’s “fight like hell”; current Georgia Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene’s “grassroots army”; Rudy Giuliani’s “trial by combat”; and Steve Bannon’s “all hell is going to break loose.”

Many of these messages expressed specific ideologies, including a deep-state conspiracy, disinformation regarding the allegedly stolen election, and white supremacy, xenophobia and racism. Ideological expression also took place without the commission of crime, and we know discourse is not a crime.

Material crimes

Material performance crimes were unco-ordinated, non-violent, non-instrumental, medium-level actions in three sub-categories:

- Occupiers — occupied desks, ate food, read papers, put their feet up, wrote threatening messages.

- Climbers — moved vertically across architectures using parkour tactics, often with police or military training.

- Thieves — ransacked the Capitol, stole lecterns, signs, laptops and other “trophies.”

These performance crimes yielded little to no strategic advantage, but garnered online fame (or infamy) by posting on social media — posts later used as criminal evidence. Material actions served to support, intentionally or otherwise, political insurrectionists.

Political crimes

Political performance crimes consisted of co-ordinated high-level actions with political objectives such as capturing and harming lawmakers, and preventing the peaceful transition of power, in two sub-categories:

- Street fighters — allegedly led by the white-supremacist, ethno-nationalist gang the Proud Boys, which led the charge against the barricades, smashed Capitol windows and fought with police.

- Insurrectionists — allegedly led by militia group the Oath Keepers. They were outfitted in flak jackets, military pants, camo, helmets, bulletproof vests and backpacks, and communicated over walkie-talkie radios and the walkie-talkie app Zello. They moved with intention in military stack formations.

Political motives

Crossover among types takes place — a self-surveillant subject might carry a sign, occupy a desk and pilfer its contents. However, not all performance crimes were represented in the media equally. Rather, increasing levels of intensity of action most often correlated with decreasing levels of self-surveillance — the more physically intensive an action was, the less likely they were to film themselves engaging in it.

The more political an individual’s objectives, the less likely they were to livestream their actions. Members of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, for example, are up on charges of seditious conspiracy but seldom appeared as self-surveillant subjects.

Pragmatically speaking, their hands were too full to livestream as they were tug-of-warring over barricades, moving in stack formation, smashing windows, and so on. But they also astutely chose not to film illegal actions, often exempting themselves from the label of performance crime.

(Sandra Jeppesen), Author provided

Incomplete and inaccurate

The filming and uploading of performance crimes during the Capitol riots is only one piece of the media puzzle. Actions were also captured from multiple perspectives by action cameras like GoPros, through reverse-camera selfie streaming, surveillance cameras and police body-worn cameras during arguably the most livestreamed mass performance crime in U.S. history.

Another piece of the news puzzle is being debated at the hearings. Did Donald Trump — a high-profile self-surveillant subject — incite violence? Did his words and actions contribute to a performance crime at the highest level?

Real-time news on social media, while promoting performance crimes, cannot be relied on to convey complex news narratives. Despite the amount of information posted online during an event (including by those participating in performance crime), what we see in real-time on social media is incomplete and inaccurate. The hearings, including recent testimony by White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson, remind us that during a political crisis, key actions occur behind closed doors.

This makes social media coverage incomplete. Conversely, social media posts may promote misinformation and disinformation, making coverage inaccurate.![]()

Sandra Jeppesen, Professor of Media, Film, and Communications, Lakehead University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.