News

Why the ‘social democratic’ SNP needs some fresh thinking after 15 years in power

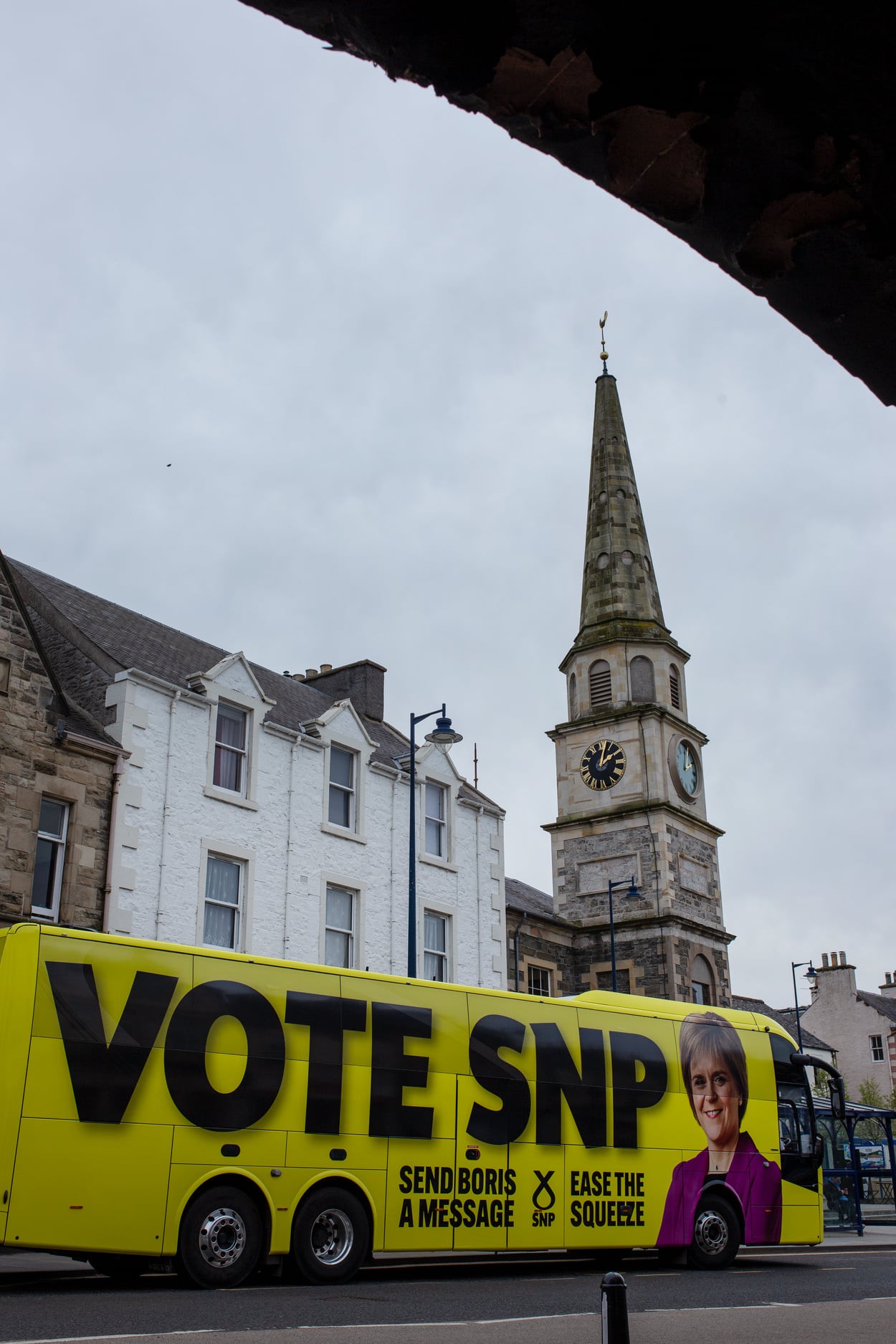

The SNP’s edge became the portrayal of itself as the last bastion of social democracy in Scotland – so-called “old Labour” territory – and a bulwark against this move to the right. (File Photo: Scottish National Party (SNP)/Facebook)

Despite growing evidence of disquiet and even discontent with the current Scottish government, the ruling Scottish Nationalist Party retains what many believe is an unassailable position of dominance after the local elections of May 2022.

There is no doubt that the opposition is still a long way behind, but the cracks are starting to appear in the notion that Scotland is a de facto “one party state” under the SNP. The announcement of the intention to hold a further referendum on independence in October 2023 is likely to crystallise these tensions further.

For the radical left to make headway in these new times, fresh thinking is needed. This is high unlikely to come from Scottish Labour as it continues to tread the path taken by previous Scottish Labour party leaders – which lost the party its position as the official opposition to the SNP government in 2016. It appears “Blairism” has made a return south of the border with Keir Starmer, and Scottish Labour has its own version of Starmer in the form of Anas Sarwar.

North Ayrshire council, a pioneer of community wealth-building as a form of local “municipal socialism”, was considered Scottish Labour’s one bright light – but the party lost control of the council on May 5022. And, as the Scottish Greens appear increasingly compromised by participating in government with the SNP, this fresh thinking is unlikely to come from them either.

The independent radical left in the form of the Scottish Socialist Party has failed to resuscitate itself after making initial headway in 2003 when it gained six MSPs and promoted ideas such as free school meals, free public transport and free prescriptions.

What is social democracy?

The revitalised ideas and ideals of social democracy are critical to being able make headway for the left. Crucially, this means being able to recognise what is and is not social democratic.

Until the mid-1990s, politics in Scotland was dominated by Labour which was then still a largely social democratic party. Social democracy is the belief in using state intervention in the economy to make capitalism’s outcomes fairer for the many. Actually applying it once in government can sometimes be problematical if there is opposition from business and the media.

Labour, north and south of the border, moved away from this belief, as Margaret Thatcher recognised. When asked in 2002 what her greatest achievement was, she said: “Tony Blair and new Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.”

The SNP’s edge became the portrayal of itself as the last bastion of social democracy in Scotland – so-called “old Labour” territory – and a bulwark against this move to the right. The SNP’s website states it is “centre left and social democratic”.

But the SNP – in government since 2007 in Scotland – has had its own conversion on the road to Damascus, in that its ideology is best now described as social liberal and not social democratic. This is most obviously indicated by its vision of an independent capitalist Scotland set out in its 2018 Sustainable Growth Commission report.

This position was not fundamentally changed by the publication in June 2022 of its new prospectus called Independence in the Modern World: Wealthier, Happier, Fairer – Why Not Scotland?

Social liberalism is based upon trying to create a successful capitalist market economy in order to raise the taxes to pay for a limited welfare state. Interference in the market is not tolerated because it is believed this might make capitalism less efficient or deter private investment and, either way, raise less tax for welfare expenditure.

This social liberalism is, of course, different from neoliberalism which seeks to deregulate the market even further and introduce it into areas where it did not previously exist via state action – in the social care sector, for example. It is this distinction between social liberalism and neoliberalism which still allows the SNP to portray itself as left-leaning, especially when compared to its two main political opponents, Scottish Labour and the Scottish Conservatives.

Changing inequalities

Social democracy of old got itself somewhat of a bad name when it became associated in the 1970s with run-down public services and state-owned industries. They were increasingly starved of the resources needed to make themselves successful and effective for servicing the wider interests of the populace. British Rail was one such example.

But this social democracy was also of the redistributive kind. Fresh thinking suggests it should be of the “pre-distributive” kind. Redistributive social democracy is a case of trying to alter the unequal effects of capitalism after the fact, through the likes of welfare benefits like unemployment or housing benefit. By contrast, pre-distributive social democracy seeks to alter the processes by which capitalism operates so that the unfair effects are far less likely to occur in the first place.

Examples are maximum wages, universal or citizen’s basic income and price controls on food, fuel and rent as well as helping create stronger unions by creating a union default system so that unions can more effectively represent their members’ interests.

Pre-distributive social democracy is more radical. While not socialism, which would see the abolition of the market and capitalism, it does attempt to deal with the problems of inequality at their root. Pre-distribution was an idea that Labour leader Ed Miliband toyed with a decade ago – albeit briefly and superficially.

It is this kind of vision that the left – whether in the SNP, Labour, Greens or outside them – must articulate if wants to appeal to the interests of the bulk of the population in Scotland, and on this basis build the political forces for radical social and economic change.

This means that the debate about independence versus enhanced devolution is a rather misleading one unless either or both sides of the pro or anti parties are prepared to promote pre-distribution. These ideas are explored in a new book published by the Jimmy Reid Foundation called A New Scotland: Building an Equal, Fair and Sustainable Society.

Independence or enhanced devolution which is not based upon pre-distribution will be another false dawn for Scottish people. It will simply repeat the flaws of the 1999 devolution settlement, which was based on the idea of the Scottish parliament acting as a shield against the unjust inequalities produced by neoliberalism without intervening in the processes of the market.![]()

Gregor Gall, Visiting Scholar, School of Law, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.