Sports

Jake Daniels: how homophobia in men’s football is changing

Blackpool forward Jake Daniels’ announcement that he is homosexual makes him the UK’s only active, openly gay, male professional footballer.

Daniels, aged 17, described the move as a “relief”, and was met with support and praise from key figures in men’s football and beyond, including Gary Lineker, Harry Kane and Sir Ian McKellen. He was also praised by national figureheads Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Prince William, who said Daniels coming out will “help break down barriers”.

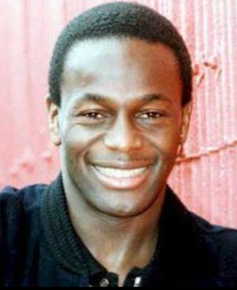

The first UK professional footballer to come out was Justin Fashanu in 1990. The support for Daniels has been a stark contrast to the homophobic responses to Fashanu, who killed himself in 1998 at the age of 37.

Sport in the UK has long been rife with homophobia and considered an unsafe place for LGBT+ players. In 2017, a House of Commons report concluded that “despite the significant change in society’s attitudes to homosexuality in the last 30 years, there is little reflection of this progress being seen in football.”

Men’s professional football is the last of the UK’s three most popular sports, following rugby and cricket, to have an active, elite professional player come out. Rugby player Gareth Thomas came out in 2009 and cricketer Steven Davies came out in 2011.

This lagging behind is no surprise given the vile homophobic chanting at some of England’s best players such as Sol Campbell, and the reaction to Fashanu in the 1990s. Indeed, there are some early signs of homophobic hate in response to Daniels that have been condemned by LGBTQ+ rights group Stonewall.

Still, over the last couple of decades, changing cultural attitudes and campaigning efforts by organisations and fans have raised awareness of LGBTQ+ participation in sport.

The Justin Campaign, established in 2008 by a Brighton-based grassroots organisation, was one of the first official campaigns to raise awareness of homophobia in men’s football. The campaign had a local reach and targeted young people, mainly school and university students who entered tournaments as team “Tackle Homophobia”.

From the Justin Campaign came Football v Homophobia, developed by PrideSports, which now has a significant presence in the game worldwide. Alongside this grassroots activism, in 2013 betting company Paddy Power, working with Stonewall, initiated the Rainbow Laces campaign.

The FA, football’s governing body in England and Wales, introduced its first anti-homophobia initiative in 2012, Opening Doors and Joining In. Since then, the FA has endorsed both Football v Homophobia and the Rainbow Laces campaigns. However, research indicates that efforts by sport governing bodies can fall short and can be ineffective at actually implementing change.

While I don’t know how aware Daniels and his peers were of these campaigns as they were growing up, there is evidence from a 2017 study at a boy’s football academy that revealed “progressive attitudes towards homosexuality” among a small group of 14-15 year olds. This suggests that attitudes are becoming more inclusive – although the boys in the study felt unable to individually challenge homophobia when they observed it.

Fan attitudes

Homophobic chanting at men’s professional games can be a common occurrence. This chanting, often deemed as “banter” by the perpetrators, can be outright blatant homophobia, or what we now call a “micro-aggression”. Micro-aggressions are the everyday speech and actions directed at marginalised members of communities that reflect prejudice and discrimination, and can be damaging to minority individuals in sport.

Obviously, not all football fans make homophobic remarks and gestures at a game or on social media. Many formal LGBTQ+ fan groups, such as the Kop Outs (Liverpool), Gay Gooners (Arsenal) and Proud Canaries (Norwich City), have also been set up in recent years, creating a visible community within the oft-discriminatory world of football fandom.

Despite these efforts by fans, football’s governing bodies continue to ignore or forget homophobia. A case in point is Qatar, host country for FIFA’s men’s World Cup later this year, which has anti-gay laws.

Cultural shifts

At 17, Daniels has grown up with a popular culture that is more diverse than ever when it comes to gender and sexuality. There are more visible stories of LGBTQ+ people and communities generally, and within the world of sport. Thanks to decades of activism, LGBTQ+ culture has a place in the mainstream, and football is benefiting from this movement.

The women’s game is further along in celebrating out lesbian and bisexual players internationally. The 2019 FIFA women’s World Cup alone had 40 out women – players, coaches and managers – offering further evidence that the women’s game is a safer environment than the men’s. This might be because women in sport have had to deal with sexist and homophobic stereotypes for a very long time.

All of this, in addition to support from family and friends and teachers, coaches, officials and managers who are LGBTQ+ allies, will make young male footballers feel safe enough to come out.

The impact of Jake Daniels’ decision to come out cannot be underestimated. Not only will it allow him to be fully himself – and perhaps an even better player – it is set to shift the culture of men’s elite professional football.

Jayne Caudwell, Associate Professor Social Sciences, Gender& Sexualities, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.