Entertainment

Bridgerton: the real 18th-century writers who used pseudonyms to stoke controversy

In the hit Netflix series Bridgerton, London society is set alight thanks to a newsletter penned by an anonymous writer whose sharp pen captures all the pomp, circumstance and gossip of the season. Fans of Bridgerton will recognise this writer, Lady Whistledown, as an integral part of the show. For viewers, she serves as our narrator. For characters, she is known as the pseudonymous author of the salacious gossip newsletter, Lady Whistledown’s Society Papers – making and breaking fortunes with each issue.

The invention of fictional “editors” to narrate similar publications was a tactic really used by 18th-century journalists and these editors could take any form, from a cantankerous Scotsman to a cosmopolitan green parrot.

Although the Lady Whistledown persona is designed to protect the papers’ secret author, she clearly takes on a distinctive life of her own. This is emphasised by the casting of Julie Andrews as the voice of the newsletter. This unique character is foregrounded further in the second season when, even after the true identity of the author has been revealed, Andrews continues to narrate the show and read the contents of the paper as Lady Whistledown. All of these dynamics are recognisable in the periodical press of the 1700s.

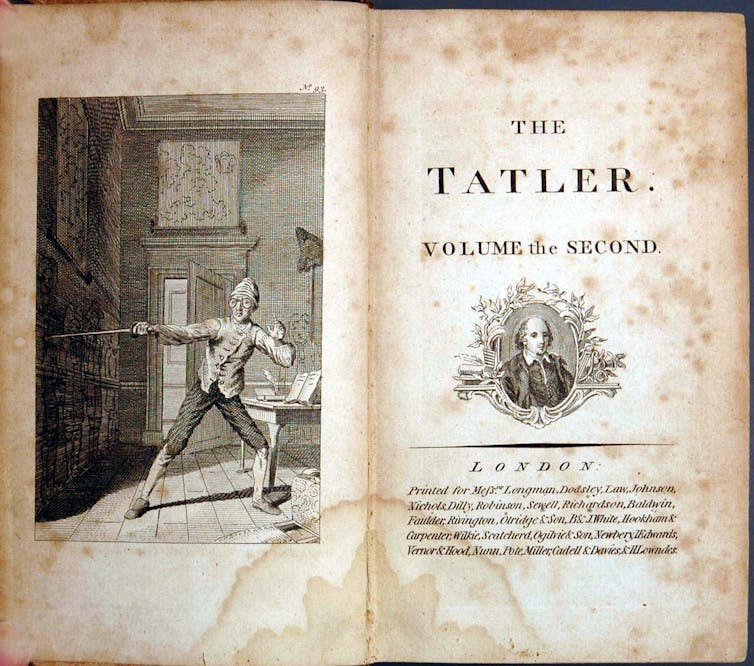

The Tatler

At the dawn of the 18th century, London society was flooded with cheap print. A highly popular form of cheap print was the literary periodical, which would usually contain a single essay and appear once or twice weekly. These essays typically contained opinions on whatever was the subject of the periodical, and there were periodicals on everything, including politics, fashion, culture and more often than not, gossip.

These periodicals were read in coffee houses and private clubs, which also provided some of the 18th-century’s best remembered periodicals with their subject matter. In 1709, for example, Richard Steele launched The Tatler. It was a periodical that promised to “to expose the false arts of life, to pull the disguise of cunning, vanity and affectation, and to recommend a general simplicity in our dress, our discourse and our behaviour”.

Like the secret author of Lady Whistledown’s Society Papers, Steele was taking on a fashionable society he was himself very much a part of. His solution was to write not as himself, but as the fictional Scottish astrologer Issac Bickerstaff.

Bickerstaff was actually invented a year earlier by Jonathan Swift as part of a year-long hoax at the expense of quack astrologer John Partridge. Steele was able to incorporate Bickerstaff’s characteristics into his own paper, while also signalling to readers the tone and approach he wished to take: one of playful, self-mocking irony and gentle satire.

Spectating society

The term coined by 18th-century scholars for this fictional editorial voice used in periodical writing is “eidolon”. Eidolons acted as an equivalent of what we might now recognise as a publication’s house style.

Readers would get to know these eidolons and in doing so come to recognise the tone and topics these periodicals would adopt. At the same time, it made it easier for other writers to contribute essays without compromising a periodical’s consistency. For instance, Steele was soon joined on The Tatler by Joseph Addison, who would similarly write essays as Bickerstaff.

Addison and Steele also collaborated on the most famous periodical of the 18th-century, The Spectator, which ran between 1711 and 1712 (the current magazine of the same name was inspired by this periodical). They wrote in this periodical as Mr Spectator, an aloof observer of mankind whose ambition was to bring “philosophy out of closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and in coffee-houses”.

Decades later, literary polymath Eliza Haywood pushed the boundaries of what an eidolon could be.

In 1747, Haywood launched The Female Spectator, a periodical loosely modelled on Addison and Steele’s original, but addressed explicitly to women. Haywood adopted not one but four eidolons: the chief editor, a beautiful and unmarried young woman, a happily married woman, and a “Widow of Quality”.

In 1746, Haywood took her experimentation even further and launched The Parrot, a periodical voiced by a non-human eidolon: a green parrot from Java. The parrot, who was taken from his home at a young age and shipped around the world by various owners before winding up in London, looked askance at behaviour he witnessed from his cage and openly championed the causes of the marginalised, be they women, supporters of the exiled Stuart king James II, or slaves.

The legacy of these literary periodicals and their curious eidolons goes far beyond the use of house styles in journalism today. They also played a role in the development of more explicitly literary forms, such as the short story and the novel, as both authors and readers learnt to engage with the notion of psychologically complex fictional constructs.

And, of course, we also see their legacy in Bridgerton. And as in Bridgerton, it was not often that these authors protected their anonymity for long (in many instances, their identity was an open secret all along). However, this rarely damaged readers’ affections for their eidolons in the long-term. So, even if we all now know who she really is, long live Lady Whistledown.![]()

Adam J Smith, Senior Lecturer in 18th-century Literature, York St John University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.