Health

How much exercise should disabled young people get? New recommendations offer advice

Being active is good for both physical and mental health. This is why evidence-based recommendations have long existed to advise people on how much exercise, and what type of exercise, they should aim to get each week in order to see these benefits.

But for years, these recommendations largely ignored the needs of people with disabilities. Though physical activity guidelines were devised for adults with disabilities in 2019, children and young people were still left unsure of how much physical activity they needed.

This uncertainty and need for evidence-based guidelines is why our team has now published the UK’s first physical activity guidelines for disabled young people aged two to 17. The recommendations we made are based on scientific research and input from disabled young people.

Creating helpful recommendations for so many different disabilities and age ranges presented a challenge to our team. This is why we looked at data from 176 different studies which investigated a broad range of physical activities (such as cycling, gymnastics, dancing or wheelchair sports) and the impact they had on the physical and mental health of young people with a range of disabilities. This included physical disabilities, intellectual and learning disabilities and sensory impairments. This allowed us to pool the best available evidence for physical activity across these groups.

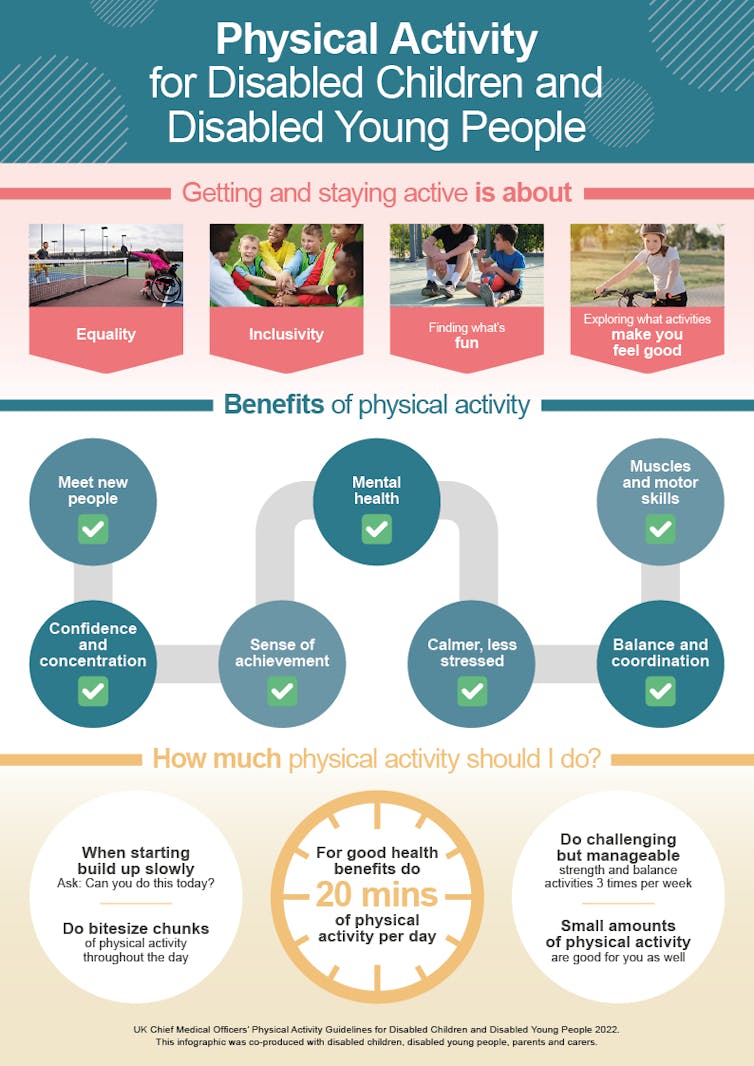

Based on our findings, we recommend that disabled young people should aim to do 120 to 180 minutes of mostly aerobic physical activity per week, whatever their age and disability – such as cycling, dance or even trampolining – at a moderate to vigorous intensity. But as the evidence showed us, this doesn’t need to be done all in one go. And though the evidence showed us that 20 minutes a day was enough to give disabled young people health benefits, that doesn’t mean they can’t do more if they would like to and are able to.

For example, it could be split into 20 minutes per day over the week, or 40 minutes only three times a week. Not only is aerobic exercise important for improving cardiovascular health, the research we looked at showed it could also help improve balance, help young people feel calmer and less stressed and may even improve confidence.

This recommendation is less than the 60 minutes of moderate or vigorous intensity physical activity each day recommended for non-disabled young people. The reason disabled young people may need less activity is because certain disabilities may mean they work harder when active due to differences in their muscle mass or the way they move.

The evidence we reviewed also showed it was important for this group to do challenging strength- and balanced-focused activities around three times per week. This could include activities like gymnastics, dancing, yoga or even playing sports. Research showed that these types of exercises could help with motor skills, build strength and endurance.

In addition, no evidence was found to show that physical activity is unsafe for disabled young people when it’s performed at a level appropriate for their age and physical and mental function. We also showed that any physical activity is better than nothing – so even small amounts could still bring health benefits.

We then shared our research with 250 disabled young people and asked their thoughts on the recommendations we made. Many told us that they’d prefer health messaging surrounding physical activity for their age group to focus more on stressing that physical activity is fun, a way to make friends and feel good.

They told us that being active meant doing bite-sized chunks throughout the day, and they still got the benefits. They also wanted to be asked if being active was right for them today and allowed to take a day off if they felt tired.

Physical activity is vital for the health of young people. It’s important for fitness, strength, mental health, functional skills or can even be a way for young people to socialise.

But achieving these physical activity targets doesn’t have to mean spending more time in the gym or doing structured workouts. Simple things like playing outside with friends, walking or wheeling to school and even tossing a ball back and forth at home are all easy ways to get chunks of physical activity into the day.

Charlie Foster, Professor in Physical Activity & Public Health, Chair of UK CMOs Expert Group for Physical Activity, University of Bristol and Brett Smith, Professor of Disability and Physical Activity, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.