Science

An exquisitely preserved egg reveals what birds have inherited from dinosaurs

Oviraptorosaurs are a group of birdlike dinosaurs that were part of the ancestral dinosaur lineage that later gave rise to birds. Oviraptorosaurs walked on two legs, had a powerful toothless beak and were covered in feathers.

One of the first known species, Oviraptor philoceratops, was discovered in the 1920s when a skeleton was uncovered alongside a nest of eggs in Cretaceous rocks of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. Paleontologists at the time assumed that the animal had died while attempting to raid the nest of another dinosaur — the name means “egg thief.”

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s, thanks to another discovery, that it was realized that the Oviraptor had actually been preserved in the act of tending to its own eggs. Since then, several important discoveries of oviraptorosaur eggs and nests have helped paleontologists reconstruct the reproductive and nesting habits of these unusual and birdlike dinosaurs.

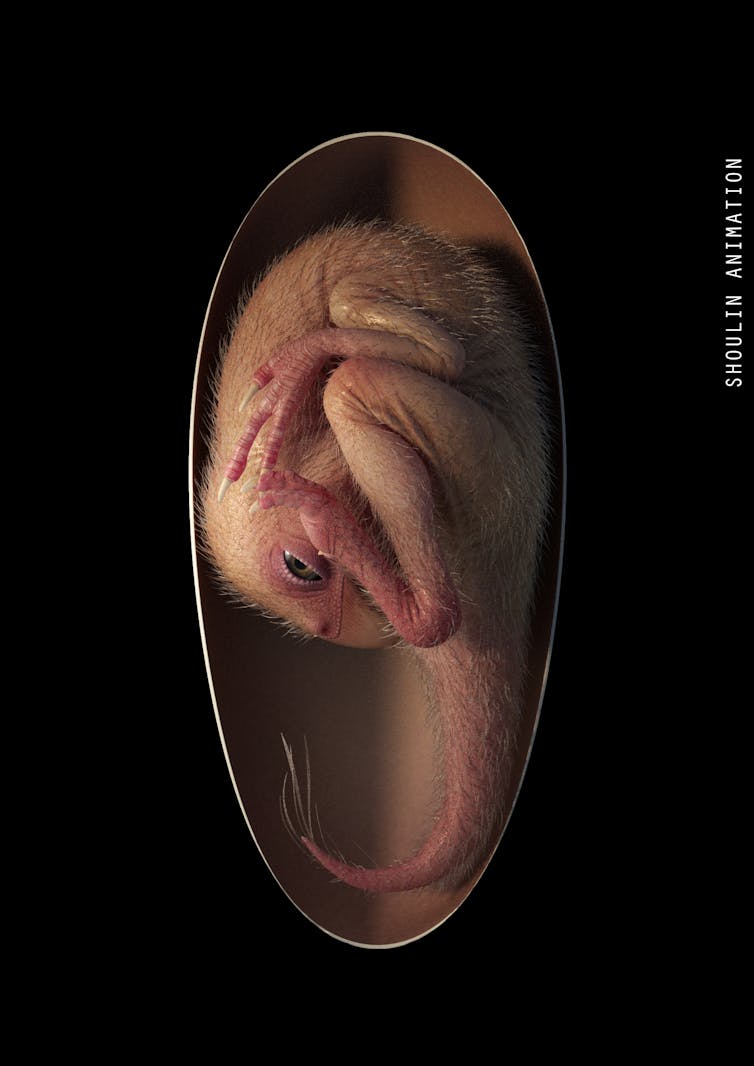

In 2021, the latest such discovery revealed an exquisitely preserved skeleton of an oviraptorosaur curled in its egg. Our group of scientists from Canada, China and the United Kingdom led the study of this 70 million-year-old fossil from China, known as Baby Yingliang.

Baby Yingliang

Baby Yingliang is the first skeleton of a baby dinosaur showing precisely how the embryo was curled in its egg. Although the remains of other embryos have been found inside eggs before, their embryonic positions were uncertain because these skeletons were disarticulated or missing many bones.

During our study of the oviraptorosaur fossil, we recognized a trait that was long considered unique to birds that relates to how the embryo is tucked in the egg before hatching. In Baby Yingliang, the back is hunched in the blunt end of the egg and its head is lying on the abdomen with the tail curled along the opposite pointed end. The legs and feet are so folded up that they are lying on either side of the head and upper body. The embryo is positioned much like a chick that is only a few days from hatching.

Bird embryos, however, are known to tuck even further than what we found in Baby Yingliang. Immediately before hatching, the head moves under the wing where it rests on the shoulder, a position that helps ensure successful pipping and escape from the egg. Perhaps Baby Yingliang would have fully tucked like a bird if it had lived a little bit longer — its overall pose still suggests that such embryonic postures first evolved in dinosaurs before being passed down to birds.

Brooding behaviours

There are also other egg-related features that birds have inherited from dinosaurs like oviraptorosaurs. These include the architecture of eggshell layers, the shape of the egg (one end is more pointed), the pigments that cause egg colour and an open nest style. Even a nesting behaviour called brooding where the parent sits on top of the eggs, long-thought to be practised only by birds, first evolved in these dinosaurs.

In a stunning fossil discovery about 25 years ago, and a few like it since, the skeleton of an oviraptorosaur parent was found crouched on top of its eggs in a bird-like fashion.

What’s interesting is that oviraptorosaurs arranged their eggs in the nest in a unique manner noticeably different from birds. The eggs, often with over 30 in a nest, were arranged in two or three stacked rings, and were oriented like the spokes of a bike tire. If these dinosaurs used body heat to incubate their eggs like today’s brooding birds, the particular layout may have been crucial to expose all eggs to the parent’s body in the central space of the ring.

The few brooding oviraptorosaur fossils that have been discovered so far are all from smaller species at around 100 kilograms or less, no bigger than the size of an ostrich. The species to which Baby Yingliang belonged would also have been about this size — the 17 centimetre egg weighed half a kilogram in life and was from an egg cluster just over half a metre across. Giant oviraptorosaurs, which are quite rare, were considerably larger, as were their eggs and nests.

Giant eggs, giant nest

In 2017, I was part of a team that studied another embryonic skeleton, known as Baby Louie. The skeleton was found with a group of eggs belonging to a new species of giant oviraptorosaur, which we named Beibeilong. As the largest known dinosaur eggs, they were over 45 centimetres long and weighed more than five kilograms each. Based on their size, the female would have weighed over 1,100 kilograms and the nest diameter was some two metres across.

Assuming Beibeilong behaved like other oviraptorosaur species, an obvious question was: How did this behemoth sit on the nest without crushing the eggs?

In 2018, with another research team, we examined the eggs and nests of oviraptorosaur species ranging from 50 kilograms to the size of Beibeilong. We found that the eggshell of the Beibeilong-sized eggs was, at two millimetres thick, likely not strong enough to withstand the animal’s entire weight.

Interestingly, we noticed that while nearly all oviraptorosaur species laid a ring of eggs with an open central space, the size of that space was relatively larger in giant species like Beibeilong. This suggested that giant species were constructing their egg ring differently from smaller species so there was plenty of space in the centre to take the brunt of the body weight, also likely reducing their contact with the eggs.

Of birds and dinosaurs

Birds acquired many of their seemingly unique features from dinosaurs. Recent discoveries of fossilized eggs and nests have revealed birdlike characteristics in oviraptorosaurs associated with reproduction.

Several features related to their eggs, including brooding behaviours, are now known to have been passed down from dinosaurs, like oviraptorosaurs, to birds. The latest discovery, Baby Yingliang, uniquely preserves the embryonic position inside its egg, one that is remarkably similar to that of a bird embryo close to hatching.

Darla K. Zelenitsky, Associate Professor, Dinosaur paleobiology, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.