News

In Latin American, not only abortions but miscarriages can lead to jail time

Georgina and I are drinking coffee on a rainy winter evening in San José, Costa Rica. She’s telling me about her abortion, “When it was over, I felt a lot of things.… But the most overwhelming feeling was relief. I was so relieved that it was over and that I wasn’t pregnant anymore. I was so relieved to be alive and not pregnant.”

Abortion is criminalized throughout Latin America, but Central American countries have some of the strictest abortions laws in the world. El Salvador has been especially notorious, with abortion banned in all cases and prison sentences if caught — you can even go to prison for having a miscarriage or a stillbirth.

Despite the severity of laws throughout the region, an estimated 6.5 million abortions take place every year, and at least 10 per cent of maternal deaths can be directly attributed to unsafe abortion.

As debates about abortion are heating up in the U.S. once again, with an almost complete abortion ban in place in Texas since September and Supreme Court hearings that have Roe vs. Wade hanging in the balance, it’s worth paying attention to the hard fought struggles over abortion in other parts of the world where, like in the U.S., religion plays a central role in politics and public life.

A “crime against life”

In Costa Rica, where I have done research on gender and sexuality for the past sixteen years, abortion laws are not quite as draconian. But Costa Rica has the dubious distinction of being one of the world’s last confessional states.

The country has a state religion, Roman Catholicism, meaning the Catholic church has an especially prominent place in public institutions like schools and hospitals. There are public debates around a variety of issues — like in vitro fertilization, euthanasia, same-sex marriage and abortion.

Costa Rica’s 1970 penal code criminalizes abortion as a “crime against life.” It is punished through jail sentences ranging between six months and three years for having an abortion, and between six months and 10 years for providing or aiding in securing an abortion.

What is called therapeutic abortion, or abortion meant to save the life or health of a pregnant person, is not criminalized, but rarely practised. It took a ruling from the Inter-American Human Rights Commission to force the country to finally establish guidelines for therapeutic abortion, but they include many complex restrictions.

Abortion research in Costa Rica

It is widely accepted that criminalizing abortion does not make abortions less frequent, it just makes them less safe. What little research there is on abortion in Costa Rica is very dated. Activists primarily rely on a 2007 study that suggested 27,000 abortions took place in Costa Rica each year.

Over the past three years, I have interviewed people who have had clandestine abortions in Costa Rica. Some had their abortions 20 years ago, others, like Georgina, had their abortions the week before I interviewed them.

One of the most notable findings of my research so far is the huge change that came with the development of medical abortion.

I interviewed Emma, a lawyer, at her workplace.

“I found out I was pregnant in 1996 and I went to see a gynecologist that everyone knew did abortions. It was a fancy private clinic in Los Yoses. He said to me ‘I can’t give you general anesthetic, so you’re going to have to keep very still. If you move and I perforate your uterus, you’ll end up in the hospital and then we’ll both end up in jail.’ It’s not like that anymore, thank god. Now you can just get some pills, it’s so much easier.”

Emma is right, abortion is changing in Costa Rica and in Latin America — networks of committed volunteers help pregnant people access mifepristone and misoprostol (abortion pills) in a variety of ways, leading to significantly reduced complications.

Younger women who have had abortions recently told about me about their deep gratitude to the strangers that helped them. Xiomara, a 22-year-old university student said: “I paid a little extra for the pills, because I could. Because you know they won’t deny them to anyone who needs them, even if they don’t have money. I was so glad that I wasn’t going to be pregnant anymore. It meant so much to me, that people I had never even met were helping me end my pregnancy, that I paid extra so that it would help cover someone else’s abortion.”

Birth no matter what

All of the people I interviewed about their clandestine abortions expressed relief at not being pregnant anymore and gratitude to the network of strangers that made it possible.

During the debates about the technical guidelines for therapeutic abortion, it became clear that many people felt strongly that pregnant people should be allowed to die rather than provided with a safe abortion.

When I interviewed Paola Vega, a deputy in the Costa Rican parliament and one of only three openly pro-choice elected officials, she said:

“The whole conversation has become radicalized. People actually argue that if a woman is dying while she’s in labour, she has to give birth no matter what happens because it’s God’s will. She has to give birth, and if she dies and if the baby dies, well, it’s God’s will. The whole discussion has gotten so much worse, so much more radical.”

A wave of young activists

The wave of young activists across Latin America who have renewed demands for access to safe, legal and free abortion has provided new hope and energy.

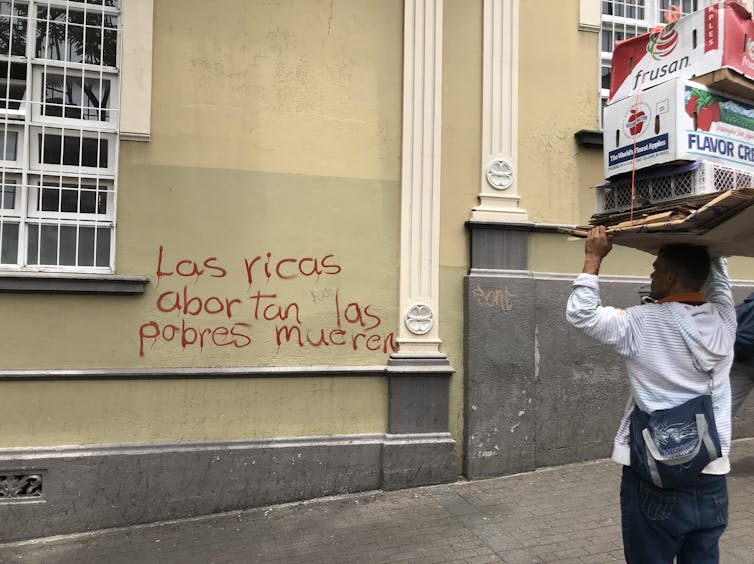

Often fighting under the slogan educación sexual para decidir, anticonceptivos para no abortar, aborto legal para no morir (sex education to be able to choose, contraceptives to not have to abort, legal abortion so we don’t die), young feminists have been at the forefront of a movement that is broad based and expansive, including anyone with a uterus and employing gender-inclusive language.

Strengthened by social media that has allowed information to be shared in real time, activists across Latin America have celebrated and gained energy from triumphs like the full decriminalization of abortion in Argentina in 2020.

In Costa Rica, corruption scandals and the pandemic have turned attention away from abortion, but with elections coming up in February, all the presidential candidates have been asked about their positions on the subject — putting the issue on the political agenda in a way that has never been before.

In the meantime, people like Mariana will continue to access abortions clandestinely:

“The person I got the pills from said I needed to take them and have someone with me. But I couldn’t tell anyway, I didn’t want my boyfriend to know, so I took the pills alone. But you know what? They called me, I don’t know who it was, a volunteer I guess. She called and stayed on the phone with me for a long time, and then called me again a few times to check on me. So it turns out I wasn’t alone. And I felt a lot of love from that stranger on the phone, I wasn’t alone.”

Megan Rivers-Moore, Associate Professor, Women’s and Gender Studies, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.