News

A disaster relief insurance system shows how well international alliances can work – new research

Rapid financial response to droughts, floods and hurricanes is critical to saving lives and livelihoods. It can prevent a disaster from escalating into a situation where people can’t get food, clean water, shelter or electricity.

But often the countries that experience these kinds of events don’t have vast reserves of money to draw on as soon as disaster strikes. Nor can they rely on international aid, which though welcome, can take weeks or even months to arrive.

Instead, many countries take out disaster insurance policies to cover the immediate costs. Haiti, for example, received a payment of around £30 million after this year’s earthquake, while Senegal was paid £16 million for drought relief in 2019.

Technically known as “disaster-liquidity insurance”, it is an innovation supported by the World Bank and donor countries such as the UK, Germany and Canada. And our research has shown that strong collaboration between countries that take out this kind of insurance has clear benefits.

This is partly because low-income countries may lack the resources to pay for insurance on their own. Multi-lateral agreements provide an effective solution.

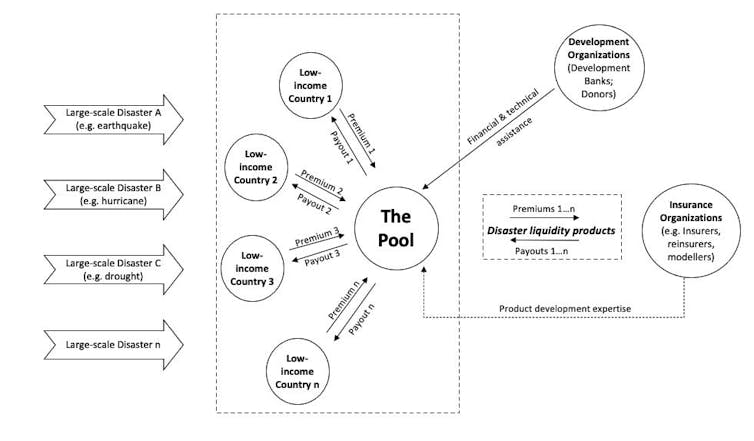

In this system, the governments of low-income countries join together to create a shared pool, enabling each country to purchase a disaster liquidity policy in a more cost-effective way.

While the pool supports a common insurance solution for a region, each country’s policy is tailored to their disaster recovery needs. Each member country determines the policy they want and how much they want to spend on it, depending on their location, disaster preparedness and capabilities.

An early financial response during the onset of drought can provide food to prevent starvation and enable vulnerable people to stay on their land.

Aside from the humanitarian benefits, immediate access to money is also economically more viable. Research has shown that a rapid response that halves the number of livestock deaths is 14 times cheaper than the cost of replacing dead animals as part of slower relief measures.

Urgent funds, paid out fast

Unlike traditional insurance, with its notoriously lengthy claims process, disaster-liquidity insurance involves contractually agreed payment triggers based on the type and severity of the disaster.

These triggers can be as specific as wind speed or soil moisture. For example, in a drought, the triggers might be browning of land captured in satellite images, combined with a reduction in soil moisture. When these conditions are met, immediate payments are made, providing a rapid injection of cash to help prevent starvation.

Such multi-lateral solutions started in 2007 with a multi-country risk pool in the Caribbean. Their success means they have spread, first to Africa, then to the Pacific and, most recently, in south-east Asia.

From 2008 to 2020, various pools have provided 78 payouts to 24 member countries, including £180 million on 54 separate events covering everything from excess rainfall to hurricanes and earthquakes in the Caribbean, and £47 million in drought relief in Africa.

For example, after Hurricane Maria in 2017, Dominica received a payment of £13 million within 14 days, enabling a critical first-line response. In 2020, Zimbabwe received combined payments of £1.2 million at the early onset of drought, allowing both direct cash disbursements and food assistance to be made to over 160,000 vulnerable families.

As one government minister told us:

We saw the pay-out after the [hurricane]. It was very quick. The president declared a state of emergency and so we put the money in an emergency budget. Then the government could use this money to respond.

A key benefit for countries is the speed of response and clarity about how much money they have, enabling them to respond effectively to protect their citizens.

After a disaster, the collaborative approach continues, with an evaluation process run by the pool that allows its members to better understand how and why certain payments were made. Our research suggests this builds confidence in disaster planning abilities for the future and strengthens the long-term viability of the pool system.

As the climate change talks in Glasgow show, agreements between governments, development agencies and financial markets are vital in addressing the disproportionate effect of climate change on countries with fragile economies and vulnerable populations.

Generating effective action from multilateral agreements is notoriously difficult. But the successes of multi-country risk pools in providing rapid insurance payouts in the immediate aftermath of disasters are a reason for optimism. They show that governments, global markets and development organisations can work together on solutions that provide much-needed help to low-income countries and vulnerable people.

Paula Jarzabkowski, Professor in Strategic Management, City, University of London; Eugenia Cacciatori, Senior Lecturer in Management, City, University of London; Konstantinos Chalkias, Senior Lecturer in Management, Birkbeck, University of London, and Rebecca Bednarek, Associate Professor, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.