News

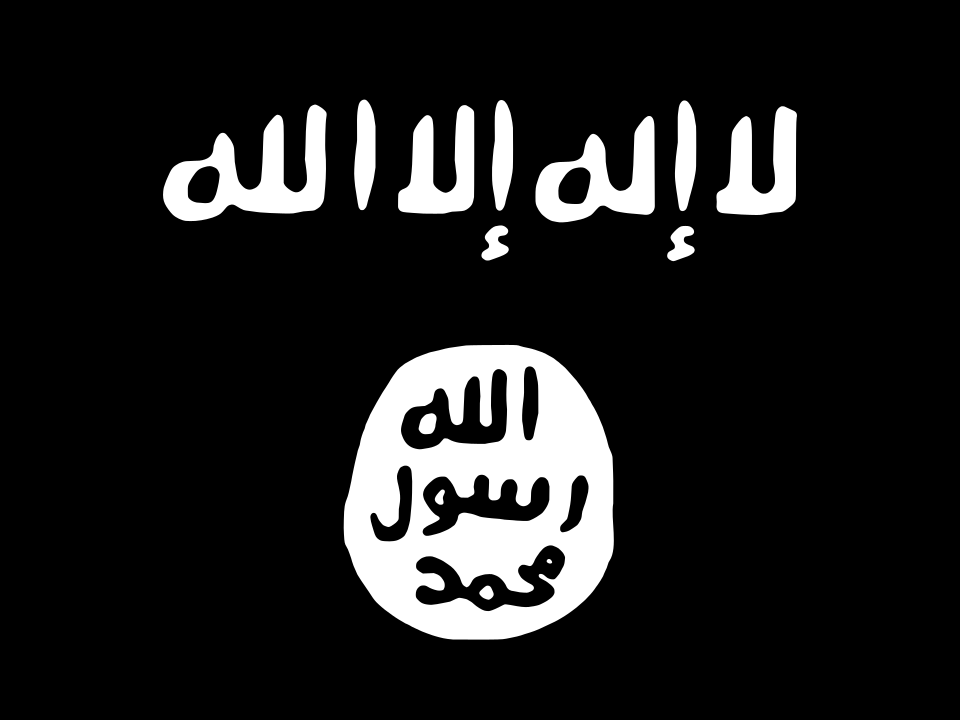

Al-Qaida, Islamic State group struggle for recruits

Al-Qaida was planning two sets of terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001. On Sept. 11, 2021, as Americans commemorate and mourn the lives lost that Tuesday morning 20 years ago, it is important to remember the second plot as well – the attacks that didn’t happen.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the organizer of the 9/11 operation, originally envisioned simultaneous attacks on the East Coast and the West Coast of the United States. He bragged about having had dozens of recruits to choose from.

But the numbers were smaller than he expected. Several people dropped out of the plot and could not be replaced. Ultimately al-Qaida could find only 19 sufficiently trained militants who were willing to die for the cause. As a result, the West Coast plot had to be canceled.

As strange as it may sound, revolutionary Islamist groups suffer from recruitment problems as any other organization does. My research on Islamist terrorism has found that al-Qaida and its rival offshoot, the Islamic State group, have long had chronic difficulties replenishing their ranks.

These groups complain about their recruitment problems frequently. “We are most amazed that the community of Islam is still asleep and heedless while its children are being wiped out and killed everywhere and its land is being diminished every day,” al-Qaida wrote in one of its online publications in 2004. It is a sentiment that the group has repeated over many years.

The Islamic State group has also expressed disappointment in Muslims’ lack of militancy. In June 2017, for example, it published an article in an online magazine criticizing Muslims who “drag the tail of shame” by remaining “safe in your homes, secure with your families and wealth” instead of joining the revolutionary movement. The problem, according to a November 2017 article in the Islamic State’s online daily newspaper, is “love of life and hatred of death,” a “disease of weakness whose final result will be the supremacy of the enemy over the Muslims.”

Democracy, not revolution

Love of life is only one of the militants’ recruitment problems.

According to social science surveys, the bulk of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims find these groups abhorrent. Most Muslims support policies that encourage or enforce Islamic piety, but they don’t support revolutionary violence. A large majority of Muslims support democratic elections, which the revolutionaries consider un-Islamic.

Democratic thought has deep roots in Islamic tradition, including the “nahda” renaissance of Arab intellectuals in the 19th century, mass pro-democracy moments in the early 20th century in the Ottoman Empire and Iran, and the Arab Spring movement that started in late 2010.

Islamist militants such as al-Qaida and the Islamic State group view democratic efforts as a threat and have repeatedly targeted pro-democracy Muslim scholars and activists for assassination. For instance, Muhammad Nu’man Fazli, a cleric in Afghanistan, was among the recent victims of this sort of violence. His mosque outside Kabul was bombed by the Islamic State group in May 2021 during a cease-fire between the Taliban and the Afghan government, specifically because of his support of democracy, according to a statement in the Islamic State group’s newspaper.

The world’s governments have made it very hard for people to find and join militant groups. There are few safe places for training, and the ones that do exist are typically in remote areas that are hard to reach, such as the mountains of northwest Pakistan, the deserts of eastern Mali, the forests of the Lake Chad basin and northern Mozambique, and the islands of the southern Philippines.

Even online, militants must constantly seek new methods to avoid detection. Every message they send or receive risks exposing them to arrest or drone attack.

Competing for recruits

Nationalist groups like Hamas, Hezbollah and the Taliban are also trying to recruit Islamic extremists. Like al-Qaida and the Islamic State group, these movements also aim to impose an austere version of Islamic law, at least partly through force of arms. But their ambitions are primarily local, as opposed to the global agendas of al-Qaida and the Islamic State group.

The nationalists and globalists may cooperate at times – most notably, the tense alliance between the Taliban and al-Qaida in the years leading up to 9/11. Still, they are fundamentally rivals when it comes to recruitment, and the nationalists are far more successful in drawing on trusted local networks.

In Afghanistan today, the Taliban have tens of thousands of militants among their recruits, according to U.S. government estimates. The Islamic State group’s regional branch, often referred to as ISIS-K, has approximately 1,000 fighters, and al-Qaida has fewer than 1,000.

Twenty years after 9/11, al-Qaida has never found enough recruits to carry out its second wave of mass-casualty attacks on America. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, only a dozen people in the United States were convicted in the years after 9/11 for links with al-Qaida, and none were involved in large-scale plots.

The Islamic State group has organized or inspired several dozen attacks in the United States, but the numbers fell off sharply in the middle of 2015, when the Turkish government closed its border with Syria. And those were do-it-yourself operations involving small arms, homemade explosives, vehicles and knives, averaging 14 fatalities per year. The Islamic State group has never mobilized enough militants in the West to “destroy the White House, Big Ben, and the Eiffel Tower, by Allah’s permission,” as it threatened to do in 2015.

Al-Qaida and the Islamic State group remain serious about targeting the United States. But the good news for Americans, on this anniversary of 9/11, is that militants face a recruitment bottleneck – a mundane organizational problem that afflicts these very unconventional organizations.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]![]()

Charles Kurzman, Professor of Sociology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.