Lifestyle

Advice for teachers on how to use the summer to protect their hearts from burnout

It’s not uncommon to hear teachers and other educators talk about being “June tired” — the way they typically feel in June after a full school year. But this year, educational workers may be experiencing a new, and much deeper, form of fatigue.

Teachers, principals and other school staff spent this past year perpetually shifting between in-school and online classrooms, worrying about vulnerable kids and often feeling guilt or hopelessness about students’ learning loss.

Read more: How to prevent teacher burnout during the coronavirus pandemic

Daily school routines included constantly wiping everything down, vigilance with enforcing social distancing, learning and instantly implementing novel approaches to in-person and online instruction — all while trying to maintain a calm and positive classroom environment and covering curriculum.

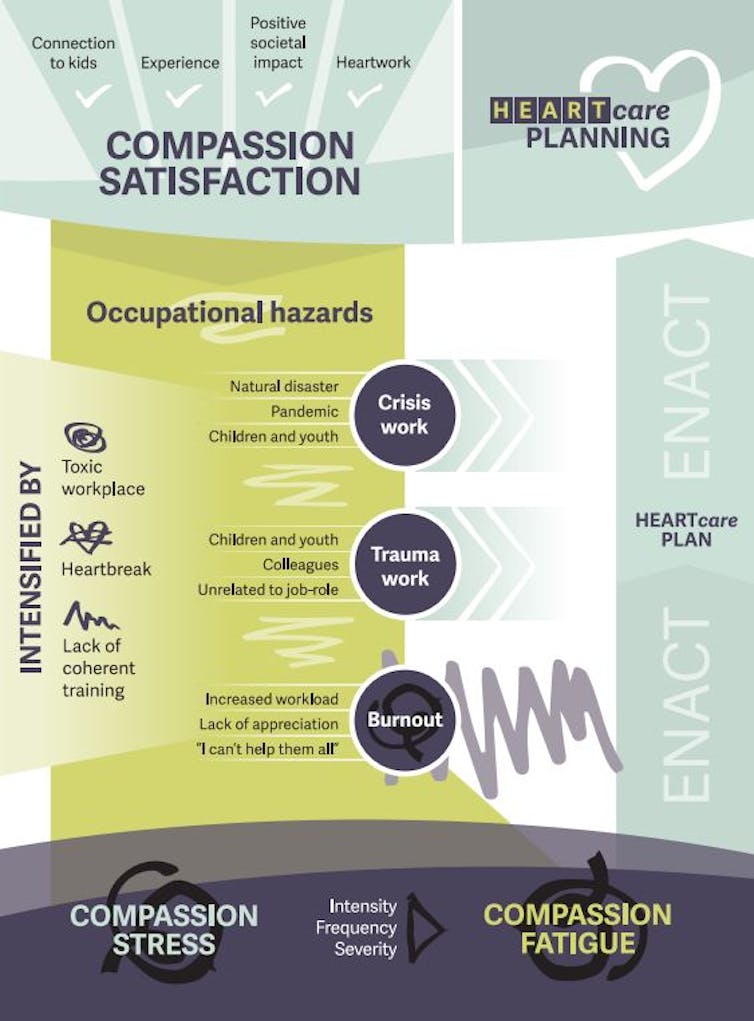

For the past 18 months, with a research team, I have been investigating the scope of compassion fatigue and burnout in Alberta’s educational workers. In education, compassion fatigue is the cost of caring, or the emotional and mental exhaustion experienced by a caregiver who deals with students who have experienced a traumatic event. Burnout is the result of long-term unmitigated stress, and both mental health problems are occupational hazards in caregiving professions.

This research study included three online surveys, with over 4,000 respondents and 53 in-person interviews to help understand the scope and experience of educational workers with these phenomena.

One main finding was that compassion fatigue was impacting the emotional health of 53 per cent of survey respondents and that 80 per cent of respondents were experiencing two or more symptoms of burnout.

The interview and qualitative survey data also indicated that educational workers were relying too heavily on self-care personal routines, like taking a bath or walking their dog, when faced with difficult and challenging workplace problems. System-wide interventions, such as administrators and policy makers taking steps to reduce educators’ daily workloads, increasing supports for inclusive classrooms and permission to take a break during the school day, are needed.

HEARTcare for educators

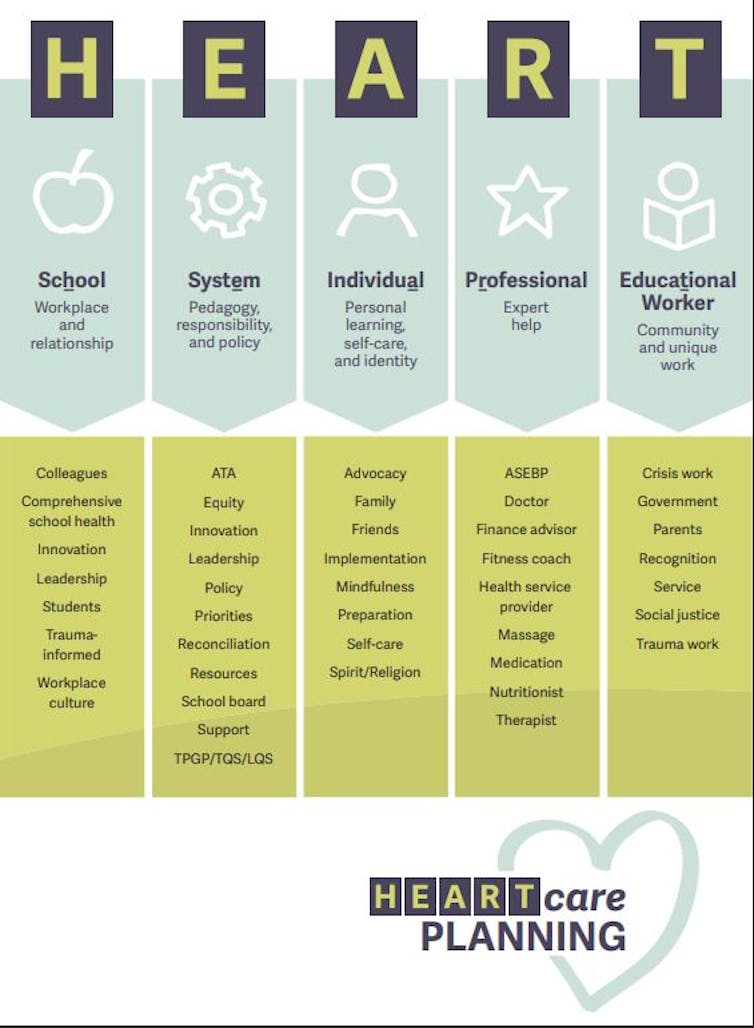

The research team started to call protecting educational workers’ emotional and mental health as protecting their “heartwork,” based on a recognition that educators’ holistic and passionate investments in their careers is a tremendous asset that also implies vulnerability. We also proposed “HEARTcare” planning: an acronym that stands for scHool, systEm, individuAl, pRofessional, educaTional worker.

HEARTcare planning suggests that workplace wellness is the collective responsibility of all levels of the educational system including school-based staff, school district leaders and personnel, elected and appointed government officials, teacher associations, educational support organizations and support staff unions.

Schools are workplaces

From educational assistants to teachers to school leaders and facility operators, school systems employ adults and can have either a positive or toxic culture. Showing compassion and empathy to colleagues and supervisors is the first step for considering the many dimensions of education that can be mobilized to protect teachers’ passion and hearts from burnout.

“I think the most challenging piece (during the COVID-19 shutdown) was that providing supports did not feel genuine because … we know that those families or those students and those teachers were struggling enormously. At times, it felt like you were just putting band-aids on things.” (Amber, school district leader)

While much attention has been paid to the influence of schools on students, individual schools do not operate in isolation from the local community, businesses or provincial government.

Individual educators may try to act as a buffer between their students and ineffective policy, the effects of poverty and racism or inadequate funding for social services. But these forces also directly affect educational caregivers’ own abilities to stay emotionally and mentally well.

Without the support of provincial and district policy-makers to address the conditions that cause children’s marginalization or their own overwork, educational workers can feel helpless or hopeless, key risk factors for compassion fatigue.

Self-care and expert help

Of course, while the larger systemic picture matters, individuals should investigate their own sources of stress and distress, and access the supports and resources available to them when they feel overwhelmed, angry or distant from the children, youth and colleagues in their circle of caring.

Educational workers also need to accept that being a good teacher or leader does not mean accepting that overwork and burnout are “just part of the job.”

While several respondents and interview participants admitted to accessing help from medical professionals, many expressed that a stigma was attached to admitting need for expert help.

However, those who did get help or took a leave to recover from trauma noted that these actions were integral to their return to positive mental health.

“I’ve given my heart, my soul, my blood, sweat and tears, and I’m only a number. If we don’t learn to take care of ourselves first, there is no way we can take care of kids.” (North, teacher)

Educational workers are worth it!

This summer, educators who are feeling emotionally, mentally and physically exhausted need to rest. Listen to your heart and do what you need to do to feel well.

“I let my work phone die over the summer, and I didn’t look at it at all. So that was good. It was a good way to set a boundary.” (Melanie, school leader)

If you are a teacher, leave your course planning until later. Turn off your worry-for-students-and-their-future brain and attune to yourself, your family, friends and what revitalizes you.

If you’re in a position of leadership, give yourself and your staff permission to leave their laptops at work and avoid sending work emails for as much of the summer as possible. Sending out the back-to-school committee agenda and checklist can wait.

If you are in upper management, consider that this upcoming year is not a great time for piloting a draft curriculum, implementing radical policy changes or changing report card software. Give yourself and your staff a chance to breathe and focus on the students next fall, not new programming.

Becoming “June-COVID-tired” was built over 18 months of hard work, enormous stress and pressure. Educators need permission to do what it takes this summer to restore, repair and reignite their hearts’ work.

Astrid H. Kendrick, Director, Field Experience (Community-Based), Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.