Food

Seafood: most Europeans struggle to identify the fish they eat – new study

How well do you know the fish you buy? Could you identify the species before it’s a fillet that you pick up in the supermarket aisle? If so, according to our new research, you’re actually more knowledgeable than most European consumers.

You can test yourself by trying to name these six commonly eaten fish:

Once you’re done – no cheating – check the answers at the bottom of the article. If you managed to identify at least two species correctly, then you’re already ahead of most British and Belgian participants in our study and on par with the European average. If you named more than three, you scored higher than most of the people we interviewed.

So why are people so estranged from the food they eat? Well, it doesn’t help that seafood sold as a particular species might be something else. New scientific tools for determining the genetic origins of produce, such as DNA barcoding, have revealed that seafood mislabelling is rampant worldwide. A recent review found that well over one-third of seafood samples from restaurants, shops and fishmongers in more than 30 countries belonged to different species than the ones they were labelled as. It wasn’t until we discovered over 60 different species of fish were being sold globally under the name “snapper” that we suspected something was off. It seems the vast majority of people buying snapper wouldn’t know such a fish if it bit them on the thumb.

Read more: How to rebrand a fish so that it sounds tastier

We reasoned that this was probably true for a lot of other popular fish species. But no research had ever estimated the average person’s knowledge of the fish they buy and eat. So, we set out to determine the level of seafood literacy among consumers in Europe.

All at sea

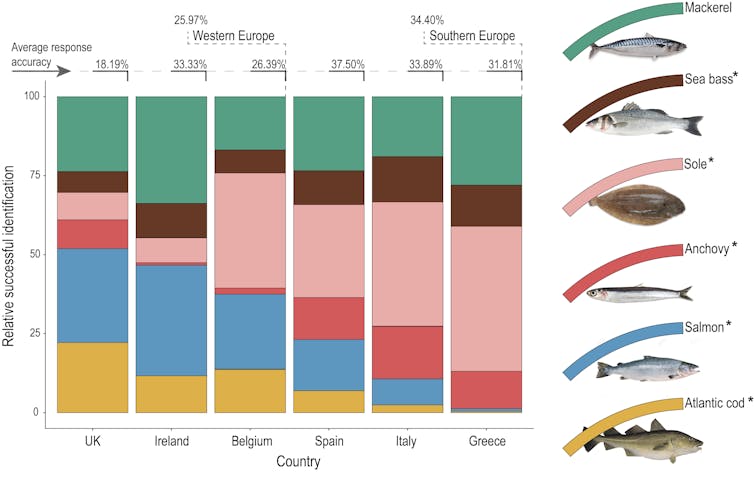

We asked 720 people from the UK, Ireland, Belgium, Spain, Italy and Greece to identify six commercial fish species from photos. People from Spain performed the best, with an average accuracy score of 38% and a little over two species guessed correctly. UK respondents did the worst, with an average accuracy score of 18% and just over one species correctly identified on average.

Most of the participants in our study struggled to identify even cod and salmon, and in a few cases threw out wild guesses, such as goldfish, stickleback, piranha and tiger shark.

This isn’t too surprising – most of us are detached from the sources of the food we eat, and fish don’t tend to roam our parks and gardens. But it may not bode well for the seafood industry or fish stocks. Previous studies have shown that people are more likely to care for a common species if they can identify it.

A glimmer of hope

Amid generally poor fish literacy, there were some encouraging geographic patterns. People from more northern countries, such as the UK, Ireland and Belgium, had an easier time identifying cod and salmon, because these fishes have long been a mainstay of their markets. Likewise, people from Spain, Italy and Greece were better at identifying anchovy, sole and sea bass.

Despite increasingly globalised supply chains – which ensure, for instance, that seabass farmed in the Mediterranean is stocked in supermarkets across northern Europe – European consumers still seem to show the legacy of an earlier era, when seafood was sourced from the closest coast. This suggests that people haven’t become completely detached from the food they consume, and instead retain some awareness of regional sea foods.

A public education campaign could build on this and reconnect more people with the species that form an important part of their diets. More knowledgeable consumers could in turn be better at making informed choices in shops and restaurants, and become less vulnerable to seafood mislabelling and fraud.

Knowing more about the seafood we eat could also equip people with a better understanding of the conservation challenges in each fishery – an important step towards safeguarding a sustainable seafood industry for generations to come. Now then, how many species did you guess?

a) Mackerel, b) Sea bass, c) Common sole, d) Anchovy, e) Salmon and f) Atlantic cod.![]()

Stefano Mariani, Professor of Marine Biodiversity, Liverpool John Moores University and Marine Cusa, Research Assistant at Liverpool John Moores University & PhD Candidate in Seafood Traceability, University of Salford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.