Entertainment

A look at the books which have inspired literary classics

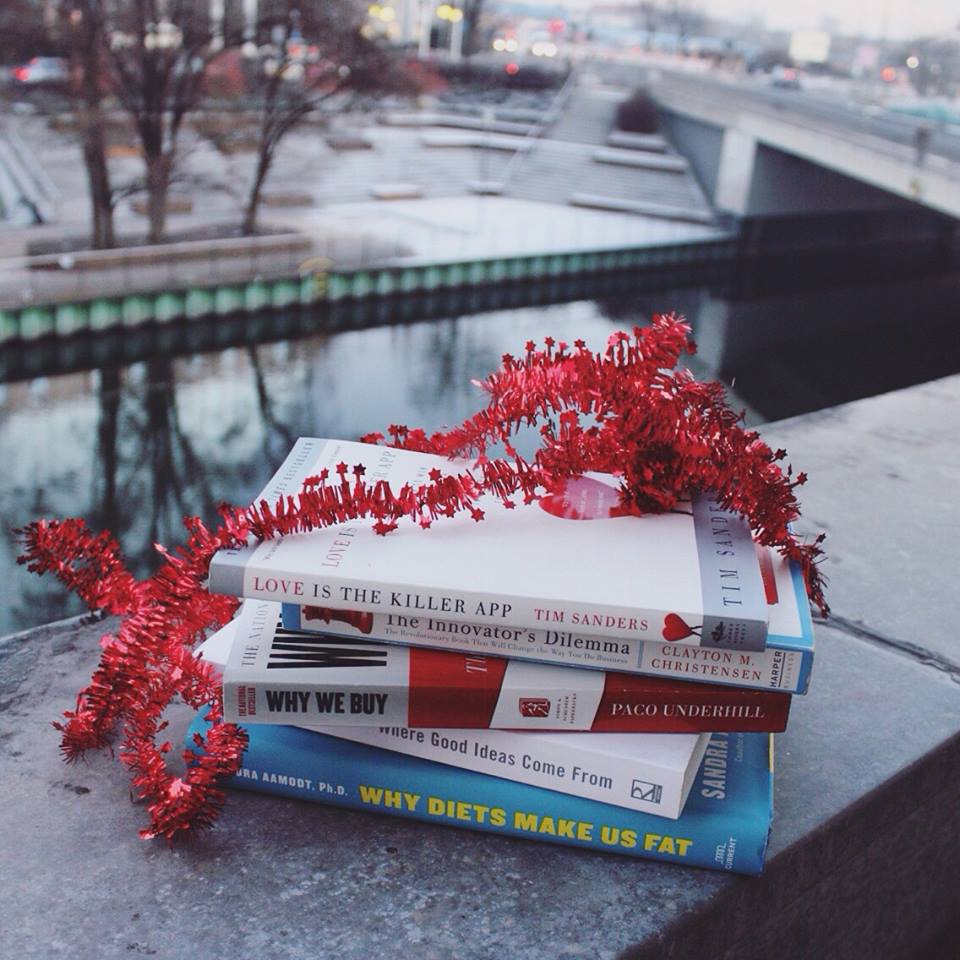

The “micro-learning” app and platform blinkist.com has been compiling literary sources for such classics as “A Clockwork Orange,” “Oliver Twist” and “1984.” (File Photo: Blinkist/Facebook)

NEW YORK — Behind every great book are the books which influenced it.

The “micro-learning” app and platform blinkist.com has been compiling literary sources for such classics as “A Clockwork Orange,” “Oliver Twist” and “1984.” Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” was inspired by each of her parents — William Godwin’s “An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice” and Mary Wollstonecraft’s “A Vindication of the Rights of Women.”

One of the defining novels of the Civil War era, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” drew in part upon one of the defining memoirs, “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.” Douglass’ book, which remains standard reading in many schools, also was cited by Toni Morrison for her Pulitzer Prize winning historical novel “Beloved.”

“We were noticing the attention around the 200th anniversary of ‘Frankenstein’ and got to thinking about the nonfiction works which help author of fiction,” says Blinkist writer-editor Tom Anderson. “We think of those books as the unsung heroes.”

Charles Dickens’ portrait of extreme wealth and poverty in London in “Oliver Twist” was in part modeled on Edward Gibbon’s “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.” Anthony Burgess drew upon fiction and nonfiction for his terrifying “A Clockwork Orange,” his sources including Aldous Huxley’s futuristic classic “Brave New World” and B.F. Skinner’s landmark of psychology “Science and Human Behavior.”

Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” reflected the author’s reading of the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, along with works about Napoleon and French history. According to Tolstoy scholar Ani Kokobobo, the author was “captivated” by Schopenhauer and his belief that “death is the only reality,” a viewpoint expressed by the cerebral Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky in “War and Peace.” Kokobobo also noted that “War and Peace” was a response in part to such French scholarship as Adolphe Thiers’ “History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon,” which Tolstoy believed exaggerated Napoleon’s stature and military ideas.

“Tolstoy did not believe in this ‘great man’ theory, also propagated by Thomas Carlyle, and thought that victory and defeat were not determined by a sole heroic leader, but rather by the collective alignment of the will of thousands,” said Kokobobo, editor of the Tolstoy Studies Journal.

George Orwell’s 1984, the Dystopian political novel which has become a bestseller again during the Trump administration, reflects in part the British author’s reading of two nonfiction studies: James Burnham’s “The Managerial Revolution” and Halford Mackinder’s “Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction.”

In a recent telephone interview, Orwell’s son, Richard Blair, said his father was “the most voracious reader” who “absorbed enormous amounts of books.” Orwell Society committee member Les Hurst said that “1984” shows how Orwell adapted the ideas of others to his own. He noted a passage from the Mackinder book, which came out just after World War I: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.” Orwell borrowed Mackinder’s framing for one of the most famous epigrams from “1984”: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

“The Mackinder book sat in Orwell’s mind for several years,” Hurst said. “Orwell was able to translate those words, able to extend Burnham’s concepts of power and power worship and to take ideals of geopolitics and perform this great imaginative leap, from geography and cast into the past and into the future. He takes something with two dimensions and turned it into something that is three dimensional.”