News

Warren ancestry highlights how tribes decide membership

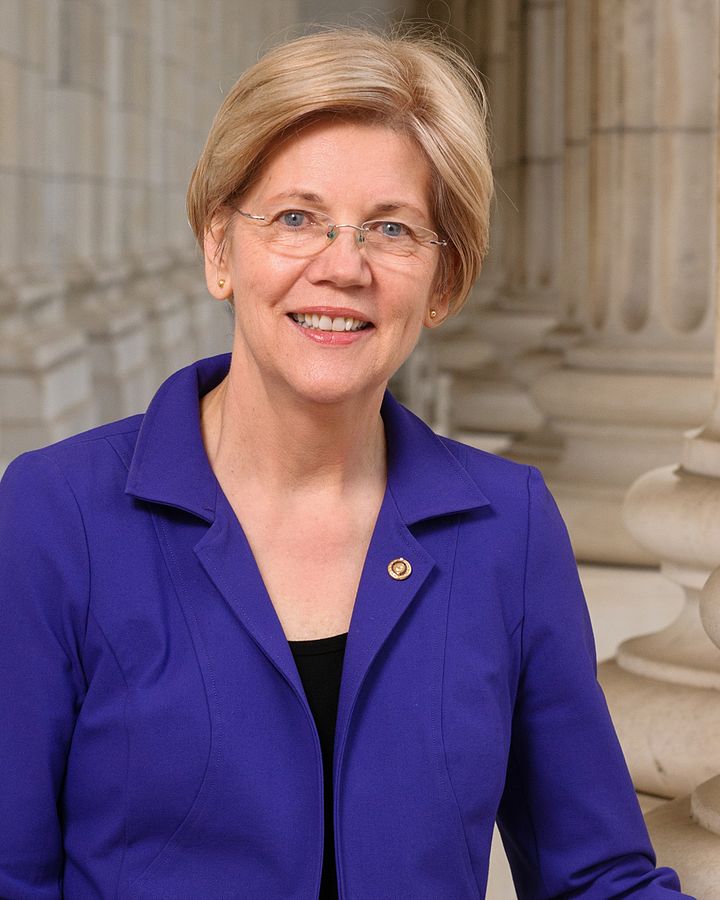

FILE: Official portrait of U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (Photo By United States Senate, Public Domain)

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. – Jon Rios traces his ancestry to the Pima people of Arizona, but he has no tribal enrolment card and lives hundreds of miles away in Colorado.

He has no interest in meeting any federally imposed requirements to prove his connection to a tribe. If anyone asks, he says he’s Native American.

“I’m a little bit like Elizabeth Warren. I have my ancestral lineage,” Rios said, referring to his affiliation with the Pima, also known as Akimel O’odham.

The clash between the Massachusetts Democratic senator and President Donald Trump over her Native American heritage highlights the varying methods tribes use to determine who belongs – a decision that has wide-ranging consequences.

Some tribes rely on blood relationships, or “blood quantum,” to confer membership. Historically, they had a broader view that included non-biological connections and whether a person had a stake in the community.

The 573 federally recognized tribes have a unique political relationship with the United States as sovereign governments that must be consulted on issues that affect them, such as sacred sites, environmental rules and commercial development. Treaties guarantee access to health care and certain social services but they can be treated differently when involved in a federal crime on a reservation.

Within tribes, enrolment also means being able to seek office, vote in tribal elections and secure property rights.

For centuries, a person’s percentage of Native American blood had nothing to do with determining who was a tribal member. And for some tribes, it still doesn’t.

Membership was based on kinship and encompassed biological relatives, those who married into the tribe and even people captured by Native Americans during wars. Black slaves held by tribes during the 1800s and their descendants became members of tribes now in Oklahoma after slavery was abolished. The Navajo Nation contemplated ways Mexican slaves could become enrolled, according to Paul Spuhan, an attorney for the tribe.

Degree of blood became a widely used standard for tribal enrolment in the 1930s when the federal government encouraged tribes to have written constitutions. The blood quantum often was determined in crude ways such as sending anthropologists and federal agents to inspect Native Americans’ physical features, like hair, skin colour and nose shape.

“It became this very biased, pseudo-science racial measurement,” said Danielle Lucero, a member of Isleta Pueblo in New Mexico and a doctoral student at Arizona State University.

Many tribes that adopted constitutions under the Indian Reorganization Act, and even those that did not, changed enrolment requirements. Blood quantum and lineal descent, or a person’s direct ancestors, remain dominant determinants.

A 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case, Santa Clara v. Martinez, upheld the authority of tribes to define their membership based on cultural values and norms. Some tribes also have used that authority to remove members.

“Historically, we have very fluid understandings of relatedness,” said David Wilkins, a University of Minnesota law professor who is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. “It was more about your value, orientation and whether or not you acted like a good citizen and a good person, and if you fulfilled your responsibilities. It didn’t matter if you had one-half, one-quarter or 1/1,000th, whatever Elizabeth Warren had.”

The Navajo Nation, one of the largest tribes in the Southwest, has a one-fourth blood quantum requirement.

The Lumbee Tribe requires members to trace ancestry to a tribal roll, re-enrol every seven years and take a civics test about prominent tribal leaders and historical events, Wilkins said.

DNA alone is not used to prove a person’s Native American background. The tests assess broad genetic markers, not specific tribal affiliations or connectedness to a tribal community.

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma uses a roster of names developed near the start of the 20th century to determine membership, regardless of the degree of Indian blood. In that era, federal agents also ascribed blood quantum to Native Americans for purposes of land ownership, Spruhan wrote.

Warren, who grew up in Norman, Oklahoma, and is seen as a presidential contender in 2020, recently released results of a DNA test that she said indicated she had a distant Native American ancestor. The test was intended to answer Trump, who has repeatedly mocked her and called her “Pocahontas.”

She has said her roots were part of “family lore,” and has never sought membership in any tribe.

Patty Ferguson-Bohnee works to protect sacred sites, culture camps and language immersion for her small Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe in southern Louisiana. The tribe also is seeking federal recognition.

“It’s not just about money, it’s about how do we protect our cultural heritage?” said Ferguson-Bohnee, who oversees the Indian Legal Program at Arizona State University.

Nicole Willis grew up hours away from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation in the Pacific Northwest, which she calls home. She travelled often from Seattle for cultural events and to spend summers with her grandmother.

To her, being Native American means her family is part of a distinct, interconnected community that has existed since ancient times. Her tribe requires citizens to be one-quarter Native American, with a grandparent or parent enrolled in the tribe, but she said “theoretically, it shouldn’t matter.

”

“We should identify with the nation that we feel a part of,” she said. “Because of the way the government dealt with us, we don’t have the benefit of ignoring the numbers aspect.”

Back in Greeley, Colorado, Rios tries to maintain traditions passed down through his father’s side and his identity by gathering medicinal plants, giving thanks for food and to his creator, sitting with family around an open fire and passing knowledge on to his daughters.

“It’s important for me and especially our people, always being respectful and trying to maintain that balance,” he said.