Canada News

Americans say Canadians delaying damning report on B.C. toxins in transboundary river

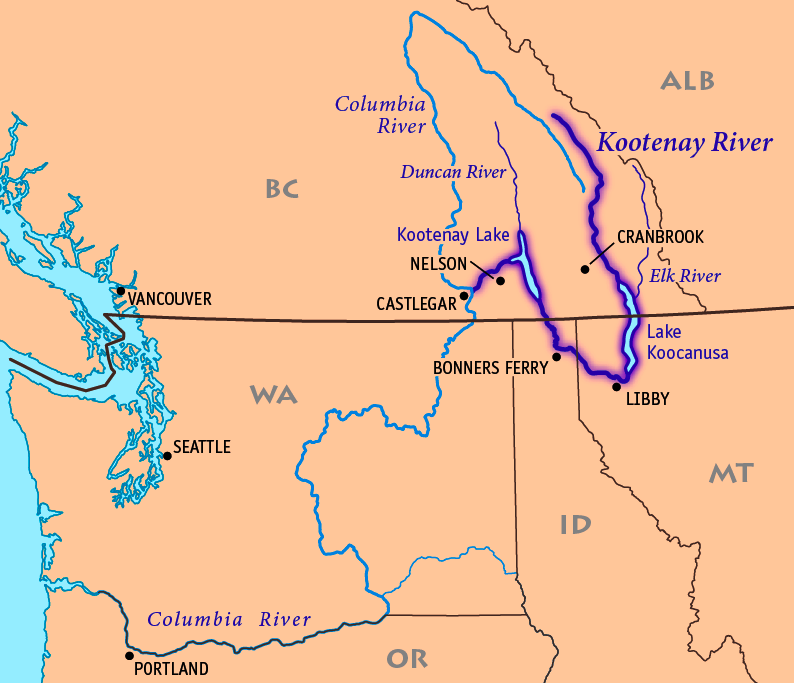

“Canadian commissioners have not been willing to submit a report that addresses selenium pollution in transboundary waters of the Kootenai River drainage,” says the letter to the State Department’s director of Canadian affairs. (Photo by: Wikimedia Commons)

United States officials are accusing their Canadian counterparts of sitting on damning new data about toxic chemicals from southern British Columbia coal mines in water shared by both countries.

In a letter to the U.S. State Department, Americans on the International Joint Commission say Canadian members are blocking the release of information on contaminants that are many times above guideline levels.

“Canadian commissioners have not been willing to submit a report that addresses selenium pollution in transboundary waters of the Kootenai River drainage,” says the letter to the State Department’s director of Canadian affairs.

The commission was created in 1909 as a way to discuss water that crosses the U.S.-Canada border.

The B.C. dispute, brewing for decades, burst open in June when the commission’s two Canadian members refused to endorse a report on selenium in the Elk River watershed just north of the border.

Trace amounts of selenium are healthy, but large doses can lead to gastrointestinal disorders, nerve damage, cirrhosis of the liver and even death in humans. In fish, it causes reproductive failure.

The report documents increasing selenium in Canadian water flowing into the transboundary Koocanusa reservoir.

All five waterways in the report have selenium levels at the maximum or above B.C.’s drinking water guidelines. Two are four times higher.

The study says the level of selenium in the Elk and Fording rivers is 70 times that in the Flathead River, which doesn’t get runoff from five coal mines operated by Teck Resources.

In May, Teck reported selenium levels in Koocanusa exceeded both human health and aquatic life guidelines.

“High selenium concentrations are resulting in deformities and reproductive failure in trout and increasing fish mortality of up to 50 per cent in some portions of the Elk and Fording watersheds,” the letter says.

Things are getting worse, said Erin Sexton, a researcher at the University of Montana. Elk River stations near the mines are reporting levels 50 times what’s recommended for aquatic health. Near the city of Fernie, B.C., readings are 10 times that level.

“The levels of selenium in the Elk are astronomical,” said Sexton.

Commission spokeswoman Sarah Lobrichon said the report is still being reviewed by commissioners on both sides.

“They’re in deliberations to consider how this new information … can complement the work of the advisory board.”

Until all agree, the report won’t go to either government, Lobrichon said.

The Americans say the delay is deliberate.

“Our Canadian colleagues prefer an earlier version of the report that is weak on addressing the recently defined impacts of selenium,” the letter says.

Teck built a water treatment plant in 2014, but its operation has been intermittent and it is currently closed. It was converting selenium into a form more easily absorbed by plants and animals.

Teck Resources said in a statement that it does extensive water testing. It said selenium levels “are appropriate and protective of aquatic life” and that fish populations haven’t been affected.

The company said it’s following a water quality plan and will spend up to $900 million over the next five years on new treatment plants.

The mines employ 4,000 workers.

An Environment Canada spokesman said new coal mine regulations are coming for toxins such as selenium.

Mark Johnson said Teck was fined $1.4 million in 2017 over selenium discharges. The company is being investigated for further violations.

“Nobody’s happy that there’s selenium in excess of water quality guidelines,” said Douglas Hill of B.C.’s Environment Department. “But we’re reasonably satisfied that Teck’s making best efforts to address the problem.”

Hill said Teck is obliged to stabilize selenium levels by the end of the decade. After that, levels are to start dropping.

Adapting existing technology to the large area and rugged landscape of Teck’s operations is challenging, said Hill.

“It’s not like they can go to Canadian Tire and buy this stuff.”

Sexton said selenium in some fish from the Koocanusa increased 20 to 70 per cent between 2008 and 2013. Montana officials surveyed fish in March for a five-year update.

“Most people anticipate there’s going to be another jump,” Sexton said.

The letter says selenium will continue to leach into rivers and groundwater for centuries if no solution is found.

“It’s financial, it’s economic, but to me it’s a poor choice to keep placing waste rock every day in that watershed and creating more surface area to leach into the river,” said Sexton.

“There’s not a consideration being made for the fish, the water or the people downstream.”