Art and Culture

Former US poet laureate Donald Hall dies in New Hampshire

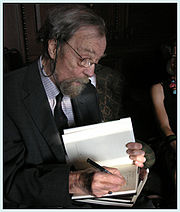

“Much of my poetry has been elegiac, even morbid, beginning with laments over New Hampshire farms and extending to the death of my wife,” he wrote in the memoir “Packing the Boxes,” published in 2008. (Photo from Wikipedia, Public Domain)

NEW YORK — Donald Hall, a prolific, award-winning poet and man of letters widely admired for his sharp humour and painful candour about nature, mortality, baseball and the distant past, has died at age 89.

Hall’s daughter, Philippa Smith, confirmed Sunday that her father died Saturday at his home in Wilmot, New Hampshire, after being in hospice care for some time.

“He’s really quite amazingly versatile,” said Hall’s long-time friend Mike Pride, the editor emeritus of the Concord Monitor newspaper and a retired administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes. He said Hall would occasionally speak to reporters at the Monitor about the importance of words.

Hall was the nation’s 2006-2007 poet laureate.

Starting in the 1950s, Hall published more than 50 books, from poetry and drama to biography and memoirs, and edited a pair of influential anthologies. He was an avid baseball fan who wrote odes to his beloved Boston Red Sox, completed a book on pitcher Dock Ellis and contributed to Sports Illustrated. He wrote a prize-winning children’s book, “Ox-Cart Man,” and even attempted a biography of Charles Laughton, only to have his actor’s widow, Elsa Lancaster, kill the project.

But the greatest acclaim came for his poetry, for which his honours included a National Book Critics Circle prize, membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a National Medal of Arts. Although his style varied from haikus to blank verse, he returned repeatedly to a handful of themes: his childhood, the death of his parents and grandparents and the loss of his second wife and fellow poet, Jane Kenyon.

“Much of my poetry has been elegiac, even morbid, beginning with laments over New Hampshire farms and extending to the death of my wife,” he wrote in the memoir “Packing the Boxes,” published in 2008.

In person, he at times resembled a 19th century rustic with his untrimmed beard and ragged hair. And his work reached back to timeless images of his beloved, ancestral New Hampshire home, Eagle Pond Farm, built in 1803 and belonging to his family since the 1860s. He kept country hours for much of his working life, rising at 6 and writing for two hours.

For Hall, the industrialized, commercialized world often seemed an intrusion, like a neon sign along a dirt road. In the tradition of T.S. Eliot and other modernists, he juxtaposed classical and historical references with contemporary slang and brand names. In “Building a House,” he begins with the drafters of the U.S. Constitution leaving Philadelphia, then shifts the setting to the 20th century.

———

Some delegates hitched rides chatting with teamsters

some flew standby and wandered stoned in O’Hare

or borrowed from King Alexander’s National Bank.

————

An opponent of the Vietnam War whose taxes were audited year after year, he was also ruthlessly self-critical. Nakedly, even abjectly, he recorded his failures and shortcomings and disappointments, whether his infidelities or his struggles with alcoholism.

The joy and tragedy of his life were his years with Kenyon, his second wife. They met in 1969, when she was his student at the University of Michigan. By the mid-70s, they were married and living together at Eagle Creek, fellow poets enjoying a fantasy of mind and body — of sex, work and homemaking.

“We sleep, we make love, we plant a tree, we walk up and down/eating lunch,” he wrote.

But Kenyon was diagnosed with leukemia and died 18 months later, in 1995, when she was only 47. Even as he found new lovers — and sought them compulsively — Hall never stopped mourning her and arranged to be buried next to her, beneath a headstone inscribed with lines from one of her poems: “I BELIEVE IN THE MIRACLES OF ART, BUT WHAT PRODIGY WILL KEEP YOU BESIDE ME?”

In the 1998 collection “Without,” and in many poems after, he reflected on her dying days, on the shock of outliving a woman so many years younger, and the lasting bewilderment of their dog Gus, who years later was still looking for her. In “Rain,” he bitterly summarized his efforts to help her.

———

I never

belittled her sorrows or joshed at her dreads and miseries

How admirable I found myself.

————

Hall was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1928, but soon favoured Eagle Pond to the “blocks of six-room houses” back home. By age 14, he had decided to become a poet, inspired after a conversation with a fellow teen versifier who declared, “It is my profession.”

“I had never heard anyone speak so thrilling a sentence,” Hall remembered.

He published poetry while a struggling student at Phillips Exeter Academy and formed many lasting literary friendships at Harvard University, including with fellow poets Robert Bly and Adrienne Rich and with George Plimpton, for whom he later served as the first poetry editor at The Paris Review. He also met Daniel Ellsberg and would suspect well before others that the anonymous leaker of the Vietnam War documents known as the Pentagon Papers was his old college friend.

After graduating from Harvard, Hall studied at the University of Oxford and became one of the few Americans to win the Newdigate Prize, a poetry honour founded at Oxford and previously given to Oscar Wilde, John Ruskin and other British writers. He returned to the states in the mid-1950s and taught at several schools, including Stanford University at Bennington College. He was married to Kirby Thompson from 1952-69, and they had two children.

Hall’s first literary hero was Edgar Allan Poe and death was an early subject. He completed his debut collection, “Exiles and Marriages,” between visits to his ailing father, who died at the end of 1955. In the poem “Snow,” Hall confesses, “Like an old man/whatever I touch I turn/to the story of death.”

In recent years, as Hall entered the “planet of antiquity,” many of his elegies were for himself. He worried that “anthologies dropped him out/Poetry festivals never invited him.” He pictured himself awaking “mournful,” dressed in black pyjamas. He warned that a story with a happy ending had not really ended, but advised that we leave behind a story to tell.

“Work, love, build a house, and die,” he wrote. “But build a house.”