Lifestyle

New technology aims to slow damage to Georgia O’Keeffe works

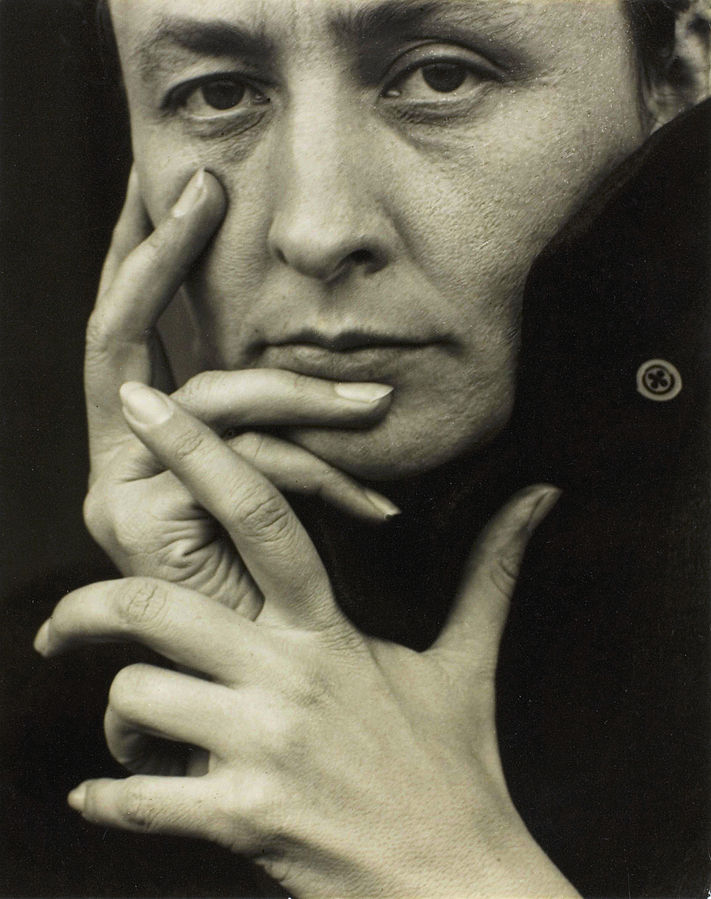

Chemical reactions are gradually darkening many of Georgia O’Keeffe’s famously vibrant paintings, and art conservation experts are hoping new digital imaging tools can help them slow the damage. (Photo By Alfred Stieglitz, Public Domain)

SANTA FE, N.M. — Chemical reactions are gradually darkening many of Georgia O’Keeffe’s famously vibrant paintings, and art conservation experts are hoping new digital imaging tools can help them slow the damage.

Scientific experts in art conservation from Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the Chicago area announced plans this week to develop advanced 3-D imaging technology to detect destructive buildup in paintings by O’Keeffe and eventually other artists in museum collections around the world.

Dale Kronkright, art conservationist at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, said the project builds on efforts that began in 2011 to monitor the preservation of O’Keeffe paintings using high-grade images from multiple sources of light. That prevented taking physical samples that might damage the works.

Destructive buildup of soap can emerge as paintings age. It happens as fats in the original oil paints combine with alkaline materials contained in pigments or drying agents.

Tiny blisters emerge in the paint and turn into protrusions that resemble tiny grains of sand and can appear translucent or white. Thousands of the tiny blemishes can noticeably darken a painting.

“They’re a little bit bigger than human hair, and you can see them with the naked eye,” Kronkright said.

The creeping problem looms not only over O’Keeffe’s iconic paintings of enlarged flowers and the New Mexico desert but also the vast majority of 20th century oil paintings in museums, in part because professional-grade canvases from the period were primed with nondrying fats or oils, Kronkright said.

To develop imaging technology that can assess the growth of the protrusions, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded $350,000 to the O’Keeffe museum and a collaborative art-conservation centre run by Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago.

The project aims to create a web-based system that allows any art conservator to upload and analyze images of paintings in efforts to limit damage from soap formation.

Scientists still do not fully understand what triggers and speeds up the formation — though changes in temperature and humidity during transportation are prime suspects, Kronkright said.

The two-year project is likely to record paintings under light frequencies that stretch beyond the visible spectrum in search of clues about the chemical composition of paintings. In the past, gathering that information would mean removing a postage-stamp-sized chip from the works.

“It now gives us a way to analyze the entire painting without taking any destructive samples whatsoever,” Kronkright said. “That’s a really big deal.”

O’Keeffe’s work offers a special opportunity to unravel the mystery of soap formation because so much is known and preserved about the techniques and materials she used on more than 800 paintings spanning a six-decade career, allowing for controlled experiments.

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum first grew alarmed about soap protrusions to its collection in 2011, when a travelling exhibit returned with visible damage that couldn’t be linked to vibrations or jostling, Kronkright said.

“Left unchecked, they will continue to grow, both grow in number and grow in size — and in damaging effect,” he said.

He estimates that five paintings in the museum’s collection have obvious damage linked to soap formation, while 90 per cent of all O’Keeffe paintings are susceptible.