Travel

Winnipeg police museum shows history of tools: from guns to hovercraft and chair legs

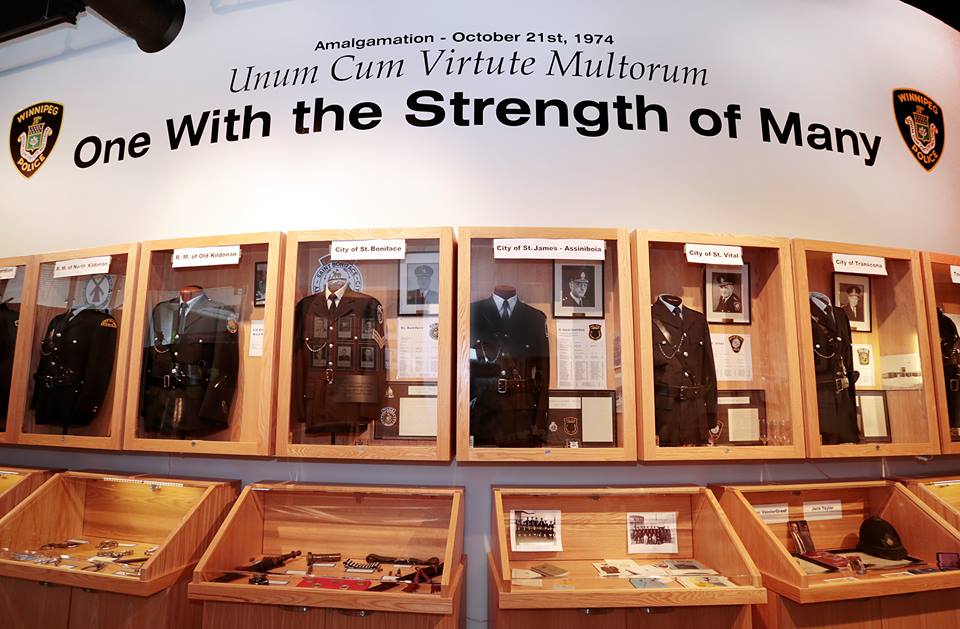

Crude leg irons. Small pellet-filled bags used as miniature clubs. Chair legs fashioned into batons. The Winnipeg Police Museum offers a fascinating glimpse into how policing evolved as the Manitoba capital grew from a small settlement on the doorstep of the West. (Photo: Winnipeg Police-Service Museum/Facebook)

WINNIPEG—Crude leg irons. Small pellet-filled bags used as miniature clubs. Chair legs fashioned into batons.

The Winnipeg Police Museum offers a fascinating glimpse into how policing evolved as the Manitoba capital grew from a small settlement on the doorstep of the West.

There were times when police officers had to work with improvised tools rather than rifles, handguns other standard fare.

The chair legs stem from an infamous moment in Canadian history — the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. Some 30,000 workers, including hundreds of police officers, left their jobs. More than 1,000 untrained special constables were brought in to bolster police ranks. They were handed chair legs because that was all that was available.

“It kind of makes sense because why would you stockpile a thousand batons,” says the museum’s curator, retired constable Randy James.

“You could cut off the legs of 250 chairs and then you have (1,000) batons.”

The museum has two of the legs on display, along with badges and arm bands worn by the special constables. There are also photographs of police officers on horse charging into the crowd on what became known as Bloody Saturday — a violent clash that injured dozens of people on both sides and claimed the lives of two of the striking workers.

James and his colleagues have managed to obtain an array of historical items from the police force, criminal seizures and private donors. There are call boxes that used to be found on city streets, medals awarded to officers by King George V, and guns ranging from a palm-sized Colt Derringer to a Thompson submachine gun with a round magazine — the kind often seen in old gangster movies.

There’s also an authentic six-foot-square holding cell from an old police station, complete with its original iron door. Stepping inside and hearing the door clang shut loudly behind you can bring a lump to your throat.

There are also police motorcycles and cars and — oddly for a non-coastal community — a hovercraft that the police force experimented with on rivers in 1971, before returning it a year later.

“Its carrying capacity is 400 pounds, so with two policeman, you’re overweight,” James says, listing one of the several shortcomings the police force discovered.

“It’s designed to come in off an ocean and across a beach, not up a steep embankment on a river, so there’s only five or six places we could get out of the river.”

The hovercraft was returned to the distributor and, 24 years later, found in a junkyard. It’s fully refurbished and functional, James says, although there is no temptation to take it out on the water.

“We’ve heard nothing good about it,” James chuckles.

Interestingly, the museum highlights both the good and the bad of the police force’s history. There is a section that shows the slow march toward equality made by women in the region’s police forces. Winnipeg had its first female officer, Mary Dunn, in 1916, but she was unarmed and dealt only with wayward children and women in distress. Female officers in Winnipeg had to wear skirts — not useful for patrol duties — for decades and didn’t carry firearms until the 1970s.

The museum also shows the stories of bad cops, such as an early police chief reportedly involved with brothels. One display in the planning stages will focus on Barry Nielsen and Jerry Stoler, two officers convicted of beating a man to death in 1981 to cover up a series of break-ins officers had committed.

“I think we have to acknowledge that police do good work and they do bad,” James says.

“And I think you have to address the bad as part of the history.”

If you go:

The Winnipeg Police Museum is located in downtown Winnipeg at 245 Smith St.

The museum is open Tuesday to Friday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Admission is free but donations are accepted.

The museum is relatively small at 3,400 square feet, but is densely packed with exhibits and memorabilia. A guided tour takes approximately 70 minutes.