Breaking

China hoping to avoid sensitive topics as G20 summit host

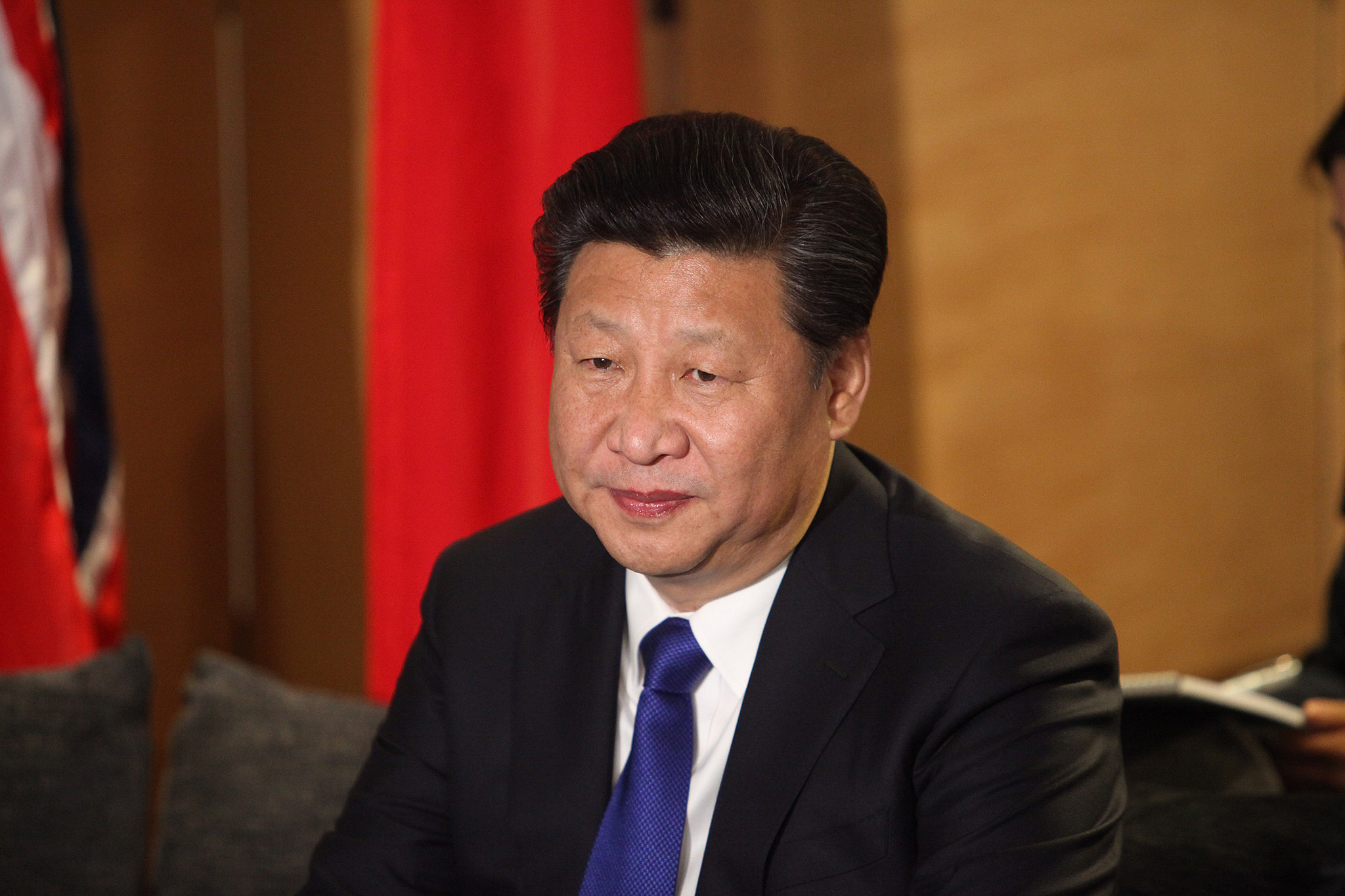

Chinese president Xi Jinping. (Photo: Foreign and Commonwealth Office/Flickr)

BEIJING—China’s hosting of the Group of 20 industrialized nations summit highlights its role as the world’s second-largest economy and a growing force in global diplomacy, but also comes amid sharpening frictions over its territorial claims in the South China Sea, disputes with fellow regional powers South Korea and Japan and criticisms over a sweeping crackdown on dissent at home.

China hopes to avoid discussion of such issues while using the summit in the eastern city of Hangzhou to burnish its image as a responsible major nation whose support is essential to solving the world’s ills. It will seek to promote its image as a force for grappling with climate change, as a promoter of development in Asia through its “One-Belt, One-Road” development drive and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and as a champion for global free trade amid the rise of economic nationalism in Europe and elsewhere.

What it wants least: Any discussion of sensitive political issues, chiefly disputes in which China appears as an aggressive revanchist power eager to erase the humiliations of the past two centuries.

“China’s main objective is to have a summit about economics, not about politics,” said Jonathan Holslag, a professor of international politics at the Free University of Brussels.

Chinese officials have repeatedly emphasized their desire to avoid controversial issues and keep the focus on the gathering’s core economic role.

“The whole country is striving for a successful and fruitful meeting to inject more impetus into the global economic growth,” Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying told reporters Monday.

Yet, its ability to control the discussions will be severely tested given the number of fractious disputes in which Beijing is now involved.

The South China Sea has become a particularly sensitive issue since an international arbitration panel in the Hague, Netherlands, in June ruled against China’s claims to almost the entire crucial water body, in a case brought by fellow claimant the Philippines. China angrily rejected the verdict and has vowed to continue developing man-made islands in the disputed Spratly islands group, while staging regular aerial patrols over the area and raising the possibility of unilaterally placing the airspace above under Chinese control.

The U.S. and others have called on Beijing to respect the ruling, and the case threatens to tarnish China’s desired image as a full-fledged member of international society.

Meanwhile, China’s ties with Japan remain tense over China’s claim to uninhabited East China Sea islands controlled by Tokyo, and its previously warm relations with South Korea have chilled in the wake of Seoul’s decision to deploy a U.S. missile defence system aimed at containing the threat from North Korea. A meeting of foreign ministers from the three countries last week produced a rare display of unity in sharply criticizing the North’s most recent submarine missile test, but did little to resolve the tensions with Beijing.

Yu Maochun, an expert on Chinese politics at the U.S. Naval Academy, said China hopes the summit will offer a chance to “find a way to extricate itself from the current diplomatic perfect storm of its own making,” while presenting itself as a “modern, prosperous, confident and gracious host.”

Outside the region, China will seek to revive a much-vaunted “golden era” in relations with Britain that have been called into question following that country’s decision to leave the European Union and David Cameron’s replacement by Theresa May as prime minister.

The summit will also be a capstone of sorts for the relationship between President Barack Obama and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping. Xi’s somewhat fuzzy concept of a “new type of major state-to-state relations” with America has been a key feature of his foreign policy, but has gained little momentum in Washington due to questions over Beijing’s approach to the South China Sea and other issues.

China will also hope that a successful summit will dampen criticism from the U.S. and European Union over sentences for subversion handed out to legal activists in a demonstration of the party’s determination to silence independent human rights workers and government critics. The activists were among about 300 people detained and questioned in July of last year, most of whom have since been released.

More broadly, under Xi, China has launched a campaign against loosely defined “anti-China forces” and Western concepts of democracy and human rights, generating what many say is a more hostile attitude toward international groups and more challenging conditions for foreign businesses.

Whatever the summit’s outcome, China is sparing no effort to ensure it goes off smoothly, relying on its experience hosting major international gatherings such as the 2008 Summer Olympics and last year’s Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation forum.

A former imperial capital, Hangzhou has a rich history and strong leisure culture, as well as being home to some of China’s best known and most innovative firms such as e-commerce powerhouse Alibaba.

A massive security presence has descended on the city and residents have been offered vouchers to get out of town. Government critics have been placed under house arrest. Restaurants run by or catering to the country’s Uighur minority have been ordered closed; extremist Uighurs seeking independence for their northwestern region have launched deadly attacks in recent years.

“The first requirement of Chinese bureaucracy is to play it safe and not take risks. It’s about projecting an image of China being comfortable at the top table,” said Steve Tsang, senior fellow at the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute.

Still, in keeping with China’s rising global profile, Tsang suggests its image might benefit from a more laid-back approach.

“It’s likely to gain more respect by showing a more relaxed and confident approach, not by demonstrating its sheer organizational might, which reinforces its authoritarian image,” he said.