Breaking

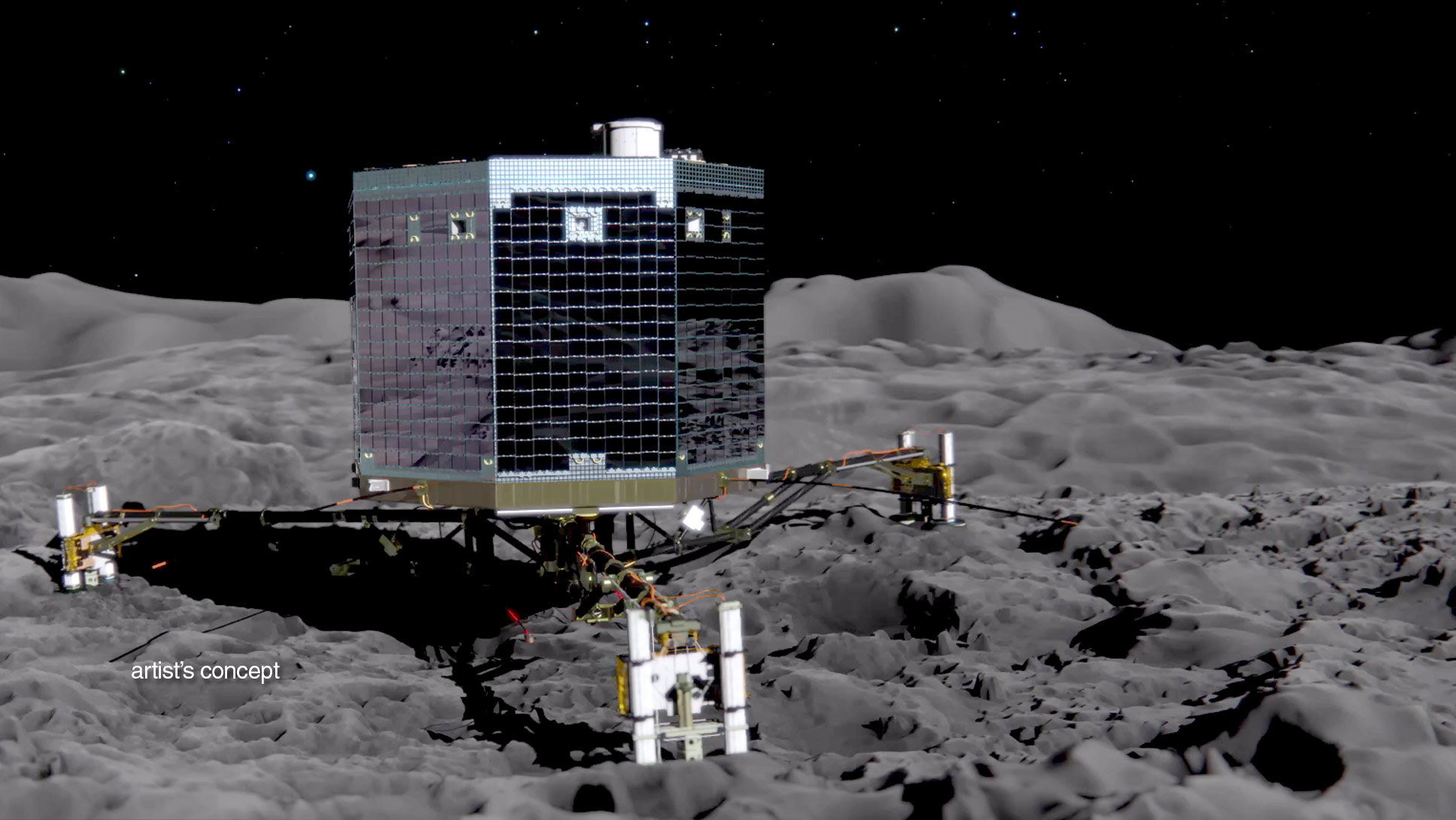

Philae probe drills into comet, turn toward light

BERLIN — The spacecraft that landed on a comet performed two tricky maneuvers Friday, by drilling into the rocky surface and rotating itself to catch more sunlight.

Both operations carried considerable risks, because they could have toppled the probe or pushed it out into the void. But without them the Philae lander that scored a historic first by touching down on a comet Wednesday risked skipping a key scientific experiment and running out of battery.

Scientists at the European Space Agency said the maneuvers appeared to have worked.

“My rotation was successful (35 degrees). Looks like a whole new comet from this angle,” read a message posted on the lander’s official Twitter account.

Earlier, the scientists tweeted: “First comet drilling is a fact!

”

Since landing on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko some 311 million miles (500 million kilometers) away, the lander has performed a series of tests and sent reams of data, including photos, back to Earth.

But with just two or three days of power in its primary battery, the lander has to rely on solar panels to generate electricity after that.

The space agency said late Friday that the batteries eventually depleted and without enough sunlight to recharge them, Philae fell into `idle mode,’ and all instruments and most of the systems on board shut down.

However, “Prior to falling silent, the lander was able to transmit all science data gathered during the First Science Sequence,” said Stephan Ulamec, lander manager.

Scientists were concerned to find Thursday that not only had Philae unexpectedly bounced twice before coming to rest untethered to the surface, but photos indicated it was next to a cliff that largely blocked sunlight from reaching two of its three solar panels.

With time running out, scientists decided to risk moving the lander and performing one of the most important experiments it was sent into space for.

Material beneath the surface of the comet has remained almost unchanged for 4.5 billion years, making the mining samples a cosmic time capsule that scientists are eager to study.

Mission controllers said Philae was able to bore 25 centimeters (10 inches) into the comet to start collecting the samples, but it’s unclear whether it has enough power to deliver any information on them.

It also wasn’t immediately clear whether the rotation had succeeded in putting the lander’s solar panels out of the shadow.

Scientists are likely to know for sure early Saturday.

Meanwhile, the Rosetta – Philae’s mother ship, which is streaking through space in tandem with the comet – will use its 11 instruments to analyze the comet over the coming months.

Scientists hope the $1.6 billion (1.3 billion-euro) project that was launched a decade ago will help them answer questions about the origins of the universe and life on Earth.

Communication with the lander is slow, with signals taking more than 28 minutes to travel between Earth and Rosetta.

“Let’s stop looking at things that we could have done if everything had worked properly,” said flight director Andrea Accomazzo. “Let us look at things that we have done, what we have achieved and what we have on the ground. This is unique and will be unique forever.”