Business and Economy

The world’s worst places for workers

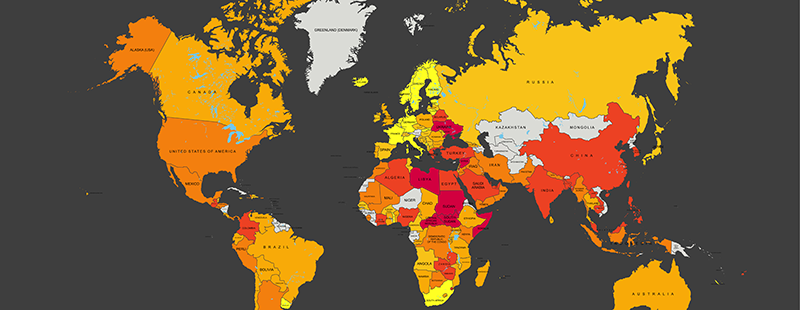

Where in the world would you choose to work, if you could? Perhaps the recently released Global Rights Index of The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) can help.

Last week, the IUTC – an alliance of regional trade confederations that advocates for labor rights around the world – published the index which ranks countries on a 1 (best) through 5 (worst) scale on the basis of how well workers’ rights are protected.

Ninety-seven indicators were used to compile the organization’s index, which revolves around the ability of workers in 139 different countries to join unions, win collective bargaining rights and have access to due process and legal protections.

The countries (shaded in dark red) in which these international norms are least respected or protected – such as large nations like India and China, and others like them which have uneven and poor labor standards, for instance – received a ranking of 5. In countries torn by conflicts and are devoid of rule of law – for example, Central African Republic, Libya or Syria – the ranking was even lower at 5+.

Gray areas on the map were not surveyed.

As for the overall survey of the state of labor in the world, the ITUC reported the following:

•Within a span of the past 12 months, governments of at least 35 countries arrested or imprisoned workers to avoid dealing with their demands for democratic rights, decent wages, safer working conditions and secure jobs.

• In at least 9 of these 35 countries, murder and disappearance of workers were used as a common method of instilling fear and intimidate the labour force.

• Some workers in petro-rich Persian Gulf states (where a great chunk of the labor work force is comprised of migrant workers) are sometimes kept in a state of feudal thralldom by employers and recruitment companies that block their ability to even move elsewhere. “In countries such as Qatar or Saudi Arabia,” the report reads, “the exclusion of migrant workers from collective labour rights means that effectively more than 90% of the workforce are unable to have access to their rights leading to forced labour practices in both countries supported by archaic sponsorship laws.”

• The US was given a low score of 4, a sign of “systematic violations” — collective bargaining rights are uneven across the U.S.’s states and unions are far weaker than some of their counterparts in northern Europe.

ITUC General Secretary Sharan Burrow said in a news release that “countries such as Denmark and Uruguay led the way through their strong labour laws, but perhaps surprisingly, the likes of Greece, the United States and Hong Kong, lagged behind.”

“A country’s level of development proved to be a poor indicator of whether it respected basic rights to bargain collectively, strike for decent conditions, or simply join a union at all,” he added.